By

Hiroaki Teraoka

(This is a reproduction of my term paper for an animal history class.)

1. Introduction

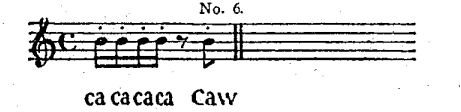

Many people have believed that some non-human animals have human like languages. Thompson (1898) is a good example of such people. He believes that crows have a language and they use this language to communicate with each other. For instance, Thompson supposes that a crow named Silverspot tells other crows about imminent danger by crying as follows:

(Thompson 1898: 68).

According to Thompson, this phrase can be translated into “Great danger—a gun, a gun: scatter for your lives” (Thompson 1898:67-68).

Although this kind of complicated translation is largely due to Thompson’s imagination, we need to consider whether non-human animals like birds really have human like languages. Furthermore, Rangarajan (2013) alludes to the possibility of lions having culture. If so, it is no wonder lions have means for communication such as language. Since language is an important property of human beings, whether non-huma species have human like language is not a tibial matter. If any non-human species have human like language, it follows that such species share humanness with us. This issue raises a question as to what makes us human. To judge whether animals have human-like languages, we need to consider properties of human language. Thus, one of the aim of this essay is to show properties of human language. Then, we proceed to compare human language and communicational means of non-human species to shed light on the anthropological question about “humanness”.

This paper proceed as follows. In section 2, we consider several different ideas in linguistic fields. In linguistic fields, there is no theory everyone agrees on even today. We take into account historical shifts in ideas in linguistics and select among these ideas an appropriate theory to analyze non-human languages. In section 3, we consider differences between human languages and non-human languages.

2. Dispute among linguistics

There has been dispute among linguistic fields over the issue as to whether non-human animals have languages. According to Chomsky (2021a, 2021b), in 1930s and 40s, the linguistic field was dominated by the idea of structural linguistics. Under structural linguistics, human language was believed to be evolved from animal communication and our first language acquisition to be habits. In other words, at that time, there was a consensus among linguists that first language acquisition was done through efforts. We repeatedly “practice” the word orders of subject-verb-object and because of these efforts, we acquire our first languages such as English, Chinese, and so on. If so, non-human animals might be able to acquire human languages through intensive trainings. According to Chomsky (2006), some researchers attempted to inculcate language into apes and all of these efforts have ended in failure. This means that the fundamental idea of structural linguistics is wrong.

In 1950s, Chomsky and his teacher, Harris proposed an alternative idea (Chomsky 2021b). Their theory was later called generative grammar. One of the fundamental supposition of generative grammar is that human beings are biologically endowed with Faculty of Language, which enables us to acquire our first languages (Chomsky 2008). In other words, generativists do not attribute first language acquisition to years of language experience of a child but to millions of years of evolutions (Ibid.). According to Chomsky (2021a), proto huma went through a significant evolutional change about 80000 years ago, which equipped homo-sapience with abilities to use language. Berwick and Chomsky (2016) claim that this evolutionarily recent change makes homo-sapience the sole species which can acquire language. A reasonable question arises here as to what change we went through.

According to Chomsky (2008), this evolutionary adaptation gave us the ability to merge. Merge is an operation which combines two objects to form one larger object (Chomsky 2008). Chomsky (2008) claims that the ability to merge gave rise to our arithmetic ability and the ability to command language. For instance, we can merge 1 and 1 and the result of the merger is 2. (Chomsky 2008). Therefore, 1+1=2 (Ibid.). Chomsky (2008) claims that addition works this way and Merge is the fundamental mechanism for arithmetic.

Although arithmetic ability is significant enough, this is just a by-product of Merge. Merger gives us the ability to command language (Chomsky 2008, 2021a). In generative field, language and thought are not to be separated. According to Chomsky (2013, 2021a), language is a thought with sounds. He maintains that thought and speech are inseparable. Therefore, species which lack thought cannot learn human-like language. Support for this claim comes from the fact that chimpanzees and other primates lack human-like language. Chomsky (2013, 2021) argues that chimpanzees and other apes have auditory system which are close to those of human beings. If so, it is no wonder they can learn language. However, chimpanzees and other primates have never shown any sign of mastering human language (Chomsky 2013, 2021a). The reason why chimpanzees cannot learn human language is that they lack human level thinking abilities (Ibid.). Chomsky (2021a) supposes that “language is essentially a system of thought” (p. 10) and language is just an externalized thought. Therefore, it seems that language and thought are closely rerated. In this respect, we come across a question as to the relationship between sounds and our thought.

In spoken languages, we use our throats and tongues to externalize languages. In sign languages, people mainly use hands and facial expressions to do so (Roberts 2021). In generative field, these externalization mechanisms are separated from true human language abilities (Chomsky 2021a). Externalization mechanisms for human language are called “Sensor-Motor (SM) medium” (Chomsky 2021a: 6). On the other hand, the true language ability of human beings is called Narrow Syntax (NS) (Chomsky 2008). Narrow Syntax and Sensor-Motor medium are dealt with separately in generative field. In Narrow Syntax, we merge constituents to form a structure and the resulting structure is sent to Sensor-Motor system to be pronounced (or signed) (Ibid.). To explain this mechanism of human language, Chomsky (2021a) uses an analogy of a computer connected to a printer. The computer with a software installed is analogized to a human brain (or Narrow Syntax). On the other hand, the printer represents Sensor-Motor Medium like our throats and tongues (or hands in the case of sign languages). As Chomsky (2021a) states, a printer does not affect a computer or software running on the computer. In the same way, our externalization medium (i.e., Sensor-Motor medium) such as our throat and tongues does not affect our language abilities. Human language ability is positioned inside our brains and it is essentially the ability to merge (Chomsky 2008). Although Merge applies relatively freely, it follows some rules made by our brains. These rules are like computer programs running on the computer which appears in Chomsky’s (2021a) analogy. The ability to merge and the rules Merge follows are called Universal Grammar (Chomsky 2021a among others). If so, we can claim that human language consists of this Universal Grammar and Sensor-Motor medium is just externalization mechanism for structures build by Universal Grammar. As we have already touched on, language is closely related to thought (Chomsky 2021a). This means that Universal Grammar represents human mind (Chomsky 2006). If we are to shed light on human language and mind, we need to consider properties of Universal Grammar (i.e., merger and rules it follows).

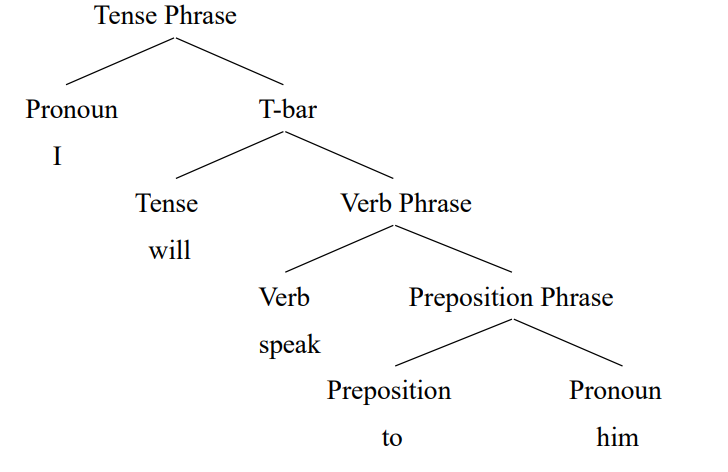

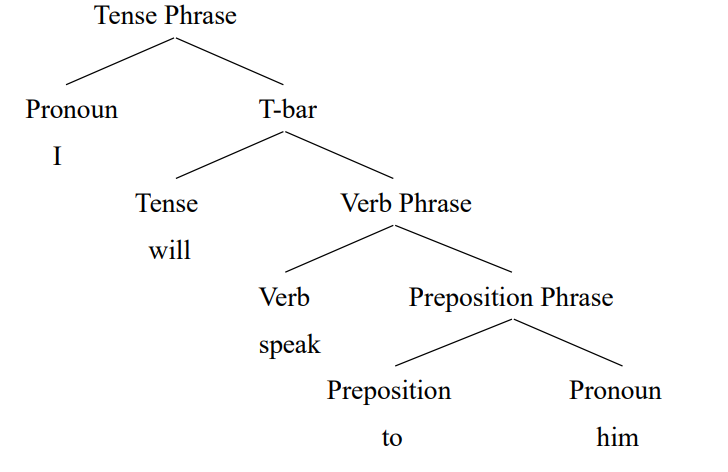

As we have already seen, Merge takes two already constructed objects and forms a single constituent from these two objects (Chomsky 2008). An important property of Merge is that it is recursive. Since Merge can only combine two constituents, merger must apply successively to form a phrase or sentence. For instance, when we build a sentence I will speak to him, merger needs to apply four times as the below diagram (1) indicates.

(1)

As a first step of the derivation, we merge the preposition to and the pronoun him to form the preposition phrase to him. This preposition phrase to him merge with a verb speak to form a verb phrase speak to him as the above tree diagram shows. The resulting verb phrase speak to him merge with a tense constituent will to form will speak to him. (Technically, this phrase is called “T-bar” since it is larger than Tense constituent will and smaller than a complete Tense Phrase. However, this is irrelevant here.) The overall phrase will speak to him is then merged with a subject I to form a complete sentence.

As the above diagram shows, Merge always combines two constituents and forms a single object. The two constituents Merge applies to are called “inputs” and the single object merger yields is named “output” (Roberts 2021). By using these technical terms, we can define recursivity of merger as follows:

(2) Merge can apply to an output.

Due to (2), successive merger yields higher and higher structures. The diagram in (1) shows successive merger has yielded a four-story object. Therefore, Chomsky (2008) argues that merger is structure building. This is another important property of Merge.

Summarizing thus far, Merge has two important properties: Merge is recursive and structure building (Chomsky 2008). Merge applies unboundedly and yields infinitely higher and higher structures. Even a sentence with one million words is possible for Universal Grammar but we get too tired to pronounce the whole sentence (Radford 1981). An important point is that this limitation is due to Sensor-Motor medium and Merger itself is unbounded (Roberts 2021). As we have already seen, Universal Grammar (i.e., the ability to merge and rules Merger abides to) represents our mind. Chomsky (2021a) even sates that human thought is a product of Universal Grammar. Therefore, unboundedness of merger has important connotations when we consider human speech and mind. Chomsky (2006) supposes that unboundedness of merger gives us freedom of expressions and thoughts. As merger applies relatively freely, we can generate novel expressions. For instance, “Look at the cross-eyed elephant!” must be a novel sentence. It is highly likely that nobody has ever uttered the exact sentence. However, it is grammatical. We can build such novel sentences due to properties of merger. As we have repeatedly emphasized, Merge gives rise to human thought. Since merger applies relatively freely and gives us the ability to make novel expressions, our thought is also novel in the same way.

Another important characteristic of human thought is that it is unbounded. Our thoughts are not restricted by anything. This unboundedness of our thought comes from unboundedness of merger (Berwick and Chomsky 2016). Since merger applies unboundedly, our thought and even language are unbounded. Since merger is so important for our mind and language, we can claim that the ability to merge separates homo-sapience from all other species on earth (Berwick and Chomsky 2016). Chomsky (2021a) claims that the only species on earth which have the ability to merge is human and this ability makes us the sole species on earth with thought. In generative field, this is the answer to the question cast in the introduction of this essay. Merger makes us the sole species on earth with language and thought and it makes us human (Chomsky 2021a).

Although generative grammar has shed some light on human language and mind, there are some backrushes against it. Linguistics has other branches and one of them is cognitive grammar. Bybee (2010) is one of proponents of cognitive grammar and she argues that human language has evolved from animal communication. This theory is quite untenable in the light of findings generative generativists have made. As Chomsky (2021a) points out, true human language ability is separated from the auditory system, as sign languages show. Sign languages are essentially the same as spoken languages (Roberts 2021). A sentence of a sign language is generated by merger of smaller parts into bigger phrases, the same way a spoken language builds a sentence (Roberts 2021). However, Bybee (2010) and other cognitive grammarians believe that human language and other animal communicational means are essentially the same. Therefore, cognitive grammarians such as Bybee (2010) claims that there is no significant qualitative differences between animal communication and human language.

The contrast between generative grammar and cognitive grammar becomes clearer when we consider how children acquire their mother tongues. Everyone agrees that we need to learn a lot of grammatical rules. An example of such grammatical rules is given below. Any English native speaker knows that himself in the below example refers to Tom.

(3) Tom blamed himself.

This is just an example of grammatical rules and any human language has a vast amount of such grammatical rules. Therefore, first language acquisition is either (i) or (ii): (i) a child rapidly learns all grammatical rules of her mother tongue after she is born; (ii) a child is born with grammatical rules and what she does after she has been born is choosing from possible options what type her language belongs to. Cognitive grammar adopts (i) and suppose a child has a vast memory (Bybee 2010). This memory enables a child to acquire her mother tongue. According to Chomsky (2021a), most children are able to utter sentences when they are three years old or younger. This means that first language acquisition progresses in a very rapid pace. If the theory of cognitive grammar is correct, it follows that a child has a truly vast memory since she needs to learn most of the grammatical rules of her mother tongue in only three years.

On the other hand, generativists adopt (ii) and believe that the amount of task for a child to do after she has been born is very small. Any human child is born with Universal Grammar and this Universal Grammar provides a child with all the necessary grammatical rules human language has. Universal Grammar came about thorough millions of evolutional adaptations (Chomsky 2008). One can claim that Universal Grammar shapes possible grammars for a human language. As we have already seen, Universal Grammar consists of the ability to merge and rules merger adheres to. Roberts (2021) supposes that each of these rules are binary and a child chooses an appropriate option from possible two options each time she is faced with a choice. These options are called “parameters” in the literature and first language acquisition of a child is none other than this parameter setting (Chomsky 1995). A child is born with these options (parameters) to choose from. For instance, we have already seen that the English language uses prepositions. A preposition is placed before a noun phrase or pronoun to describe a direction and so on. There are languages which employs postpositions, which are counterparts of prepositions. Postpositions follow noun phrases and pronouns and describes almost the same concepts as prepositions. Thus, the difference between a preposition and postposition is the positions in which they are placed. Therefore, generativists suppose that we human beings are born with the concepts of prepositions and postpositions and here we introduce the notion of a parameter. A child is faced with the task of choosing whether her language is preposition type or not. As the above diagram (1) shows, a preposition merges with a noun to form a preposition phrase. A child growing up in the U.K., U.S. and other English speaking countries hears adults around her use preposition phrases and thus sets the value of the parameter as “preposition.” On the other hand, a child who grows up hearing Japanese sets the value of the parameter as “not preposition.” In this fashion, generative grammarians explain why first language acquisition of a child is done at a so rapid pace. A child already knows what prepositions and postpositions are and they just decide which one her mother tongue adopts. Similar mechanisms apply to other grammatical categories such as verbs and wh-question words. For instance, generativists suppose that a child knows what wh-question words are and they just decide whether the wh-question words remain in-situ (i.e., in their original positions) in question sentences like in Japanese or are fronted like in English (Roberts 2021).

Summarizing thus far, we linguists need to explain mysteries concerning first language acquisition. Most children succeed in first language acquisitions regardless of their IQ and they learn the languages in rapid paces. Proponents of cognitive grammarians believe that a child has a really good memory. On the other hand, generativists suppose a child is born with Universal Grammar and what she does is just choosing a possible grammar allowed by Universal Grammar.

In the following section, we analyze language of non-human species by adopting theories of generative grammar. This is because only generative grammarians can mention properties of human language accurately. Adopting generative theory enables us to shed light on what kind of differences human language and languages of non-human species have.

3. Do non-human species have languages?

In this section, we address the question whether non-human species have languages. If non-human species have languages, we try to consider differences between human languages and nun-non-human languages.

Rangarajan (2013) alludes to the possibility of larger animals such as lions having cultures. Given this, it is no wonder some animals have languages. Chimpanzees and other apes are very good candidates since their cognitive abilities seem to be close to those of human beings. However, as Chomsky (2021a) states, despite enormous efforts to inculcate human language into chimpanzees, they show no sign of mastering human language. This fact buttresses Chomsky’s (2021a) claim that animal communication and human language are totally different and human language is essentially our thought. We human beings use language primarily as a tool for thought and secondarily as a means of communication (Chomsky 2006, 2021a). Chomsky (2021a) continues that species which lack human thought cannot acquire human languages.

Other non-human species which are believed to have languages are dolphins and whales. Jones (2013) states that whales communicate with each other across a far distance. This kind of observation leads one to argue that whales and dolphins have human-like languages. However, Chomsky (2006) rebuffs this notion as an unfounded myth. Even though dolphins and whales communicate with each other, their languages lack creativity we can observe in human languages. As we have already seen, Merge can apply unboundedly and relatively freely. These characteristics of merger make our language and thought creative and unbounded (Chomsky 2006). As we have already seen, we can make novel expressions such as “a cross-eyed elephant.” This fact means that we do not rote memorize our parents’ speech. We have Universal Grammar and can create sentences allowed by the rules of Universal Grammar. On the other hand, languages of whales and dolphins do not have this level of creativity (Chomsky 2006). Their language is not a tool of thought as our language is (Ibid.). Therefore, neither whales nor dolphins have human level language abilities or human level thought.

Here, we need to introduce important concepts proposed by Hauser, Chomsky and Fitch (2002). Hauser et al. (2002) suppose that there are two types of languages and each of them has a different fundamental system. Hauser et al. (2002) claim that although many non-human species have Faculty of Language in a Broader sense (FLB), only human beings have Faculty of Language in a Narrow sense (FLN). Faculty of Language in a Broader sense (FLB) consists of an auditory or non-auditory communicational means. This mechanism loosely corresponds to our Sensor-Motor medium (such as our throats, tongues, lips and hands for signers) in human language. Many non-human species can communicate within the species using this system. In the case of bees, they move around in front of the exit of the beehives to show other bees the direction of flower beds. For this communicational means to work properly, bees which shows the way to the flower bed must use their bodies (or wings) and the bees which interpret the message need to use their eyes. These systems seem to be what Hauser et al. (2002) call Faculty of Language in a Broader sense and this loosely corresponds to our Sensor-Motor medium (i.e., externalization mechanisms for human language). However, bees and other species do not use their languages as tools for thinking or planning, as we do (Chomsky 2021a). This thinking ability is what species with Faculty of Language in a Broader sense lacks.

On the other hand, Faculty of Language in a Narrow sense consists of the Sensor-Motor system and Narrow Syntax (i.e., Universal Grammar) (Hauser et al. 2002). Although human and most non-human species both have Sensor-Motor mediums, non-human species lack Narrow Syntax. Thus, non-human species cannot merge anything or do not have rules merger adheres to. Since the ability to merge and properties of Merge are tools of our thought, non-human species lack human level creative, unbounded thought. Whales and dolphins do not have Universal Grammar either. This means that their languages are just communication medium and they do not use their languages as tools for thought and plaining as we do (Chomsky 2021a).

In the light of this finding, we carefully consider the language of birds. As some finches have complicated communicational means, language of birds is the most likely candidate which may be comparable to human language. Okanoya (2013) states that some finches have their mother tongues and foreign languages. Finches which have been brought un in a particular area pick us a song and these finches cannot acquire songs of finches brought up in other areas (Okanoya 2013). In this regard, bird songs and human language are very similar. However, the similarities end here. Okanoya (2013) states that bird songs lack syntax observed in human language. In other words, language of birds is totally different from human language.

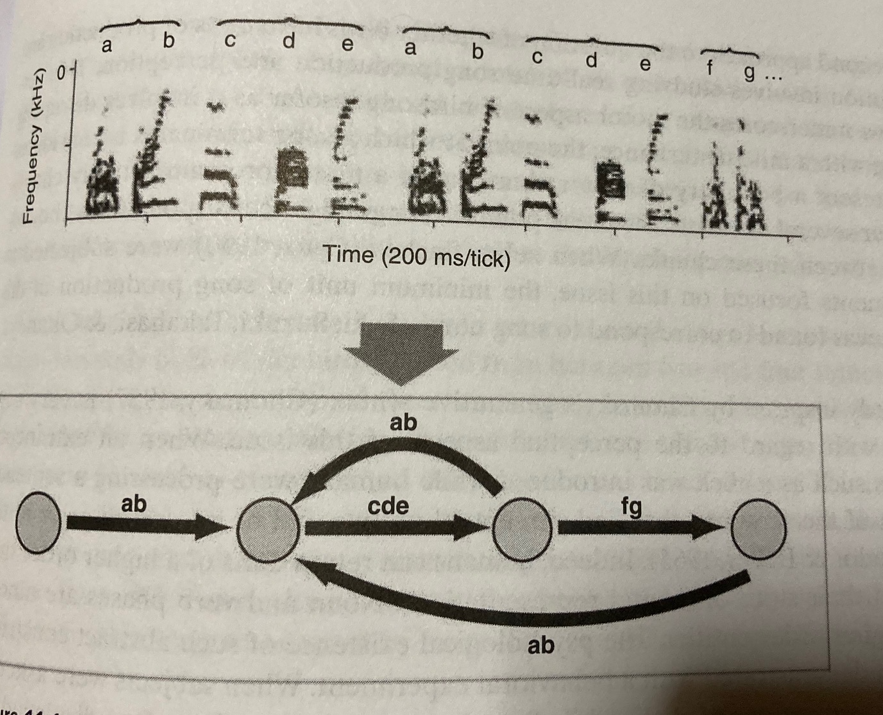

Okanoya (2013) studies songs of Bengalese finches. He collects the below data (4).

(4)

(Okanoya 2013: 231)

According to Okanoya, the upper graph represents the actual sound of a Bengalese finch and in the lower diagram, he analyzes the song. As Okanoya (2013) observes, the song starts with “ab” and then proceeds to “cde”. After that, the bird just repeats “ab” and “cde” in this order. After this, the bird proceeds to “fg”. This song is repetitive and lacks recursivity observed in human language. As we have already seen, recursivity is one of the important characteristics of human language. The tree diagram in (1), repeated here as (5), shows this point.

(5)

The preposition to and pronoun him marge and form a preposition phrase to him. Since Merge is recursive (i.e., merger can apply to its output), the resulting phrase to him is merged with a verb speak to form a verb phrase speak to him. In this fashion, the phrase gets larger and larger and the preposition phrase to him is embedded in a deeper and deeper position. Since merger is unbounded, the preposition phrase to him can be embedded in an infinitively deep position. In contrast to this, the “syntax” of bird song is repetitive and lacks embedding. Neither “ab” nor “cde” is deeply embedded in the resulting structure. One can even claim that the “syntax” of birds lacks structure. More accurately, {ab} and {cde} do not merge. Thus, {ab} and {cde} do not create a constituent {{ab} {cde}}. If {{ab}{cde}} were a constituent, the phrase as a whole would merge (i.e., combine) with the following part and result is a higher structure. However, in reality, the bird seems to rely on just liner orders but not build a structure. Thus, the “syntax” of bird songs is different from that of human language in that birds cannot merge. Therefore, bird songs lack structures observed in human languages.

Summarizing thus far, we have considered possibilities of non-human species having human-like languages. As Hauser et al. (2002) argue, language faculties of all the species can be categorized into Faculty of Language in a Broader sense and Faculty of Language in a Narrow sense. Although both of them have Sensor-Motor medium in common, only Faculty of Language in a Narrow sense has Universal Grammar. Since Universal Grammar (i.e., the ability to merge and rules merger follows) is essentially our thought mechanism and only human beings are endowed with Universal Grammar, Hauser et al. (2002) claim that only human beings have Faculty of a Language in Narrow sense. Although some non-human species communicate within each species, only human beings use languages as tools for thought and planning not just for communication.

4 Conclusion

Some people have believed non-human species have languages. In a broader sense, their belief might turn out to be true. Some species such as whales and birds can communicate within the species in rudimentary ways (Okanoya 2013, Jones 2013). However, their “languages” are far from human language. Generative grammarians believe that Merge is the fundamental human language ability. Merge applies unboundedly and this property of merger makes our speech unbounded and creative. Chomsky (2021a) supposes that language is essentially the system of thought. This means that our thought mechanisms are also unbounded and creative. Non-human languages lack this unbounded and creative aspects and these species do not show any signs of using their languages as tools for thought and plaining as we human beings do. Therefore, we human beings are the sole species which are endowed language which supports thought and this fact makes us human.

References)

Bolhuis, J. J. and M. Everaert (eds.) (2013) Birdsong, Speech, and Language: Exploring the Evidence of Mind and Brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Berwick, R. C. and Chomsky, N. (2016) Why Only us: Language and Evolution. Cambridge, MA. MIT Press.

Bybee, J. (2010) Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1955) “Transformational Analysis.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Chomsky, N. (1975a) The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory. New York: Plenum.

Chomsky, N. (1995) The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2006) Language and Mind. 3rd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N, (2007) “Approaching UG from Below.” In Sauerland, U. and Gärtner, H-M. (eds.) Interfaces + Recursion = Language?: Chomsky’s Minimalism and the View from Syntax-Semantics. Berlin; Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 1-29.

Chomsky, N. (2008) “On Phases.” In Freiden, R., Otero, C. P. and Zubizarreta, M. L. (eds.) Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory: Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp.133-166.

Chomsky, N. (2013) “Lecture I: What is language?” The Journal of Philosophy, 110: 645-662.

Chomsky, N. (2021a) “Minimalism: Where Are We Now, and Where Can We Hope to Go.” Gengo Kenkyu, 160: 1-41.

Chomsky, N. (2021b) “Linguistics then and Now: Some Personal Reflections.” Annual Review of Linguistics, 7: 1-11.

Hauser, M. D., N. Chomsky, & W. T. Fitch (2002) “The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve? Science, 298: 1596-1579.

Jones, R. T. (2013) “Running into Whales: The History of the North pacific from below the Waves.” American Historical Review: 349-377.

Okanoya, K. (2013) “Finite-State Song Syntax in Bengalese Finches: Sensorimotor Evidence, Developmental Processes, and Formal Procedure for Syntax Extraction.” In Bolhuis, J. J. and M. Everaert (eds.) (2013) pp. 229-242.

Radford, A. (1981) Transformational Syntax: A Student’s Guide to Chomsky’s Extended Standard Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rangarajan, M. (2013) “Animals with Rich Histories: The Case of the Lions of Gir Forest, Gujarat, India.” History and Theory, 52: 109-127.

Reuland, E. (2013) “Recursivity of Language: What Can Birds Tell Us about It?” In Bolhuis, J. J. and M. Everaert (eds.) pp. 209-228.

Roberts, I. (2021) Diachronic Syntax. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ten Cate, C., R. Latulan, and W. Zuidema (2013) “Analyzing the Structure of Bird Vocalizations and Language: Finding Common Ground.” In Bolhuis, J. J. and M. Everaert (eds.) (2013) pp. 243-260.

Thompson, E. S. (1898) Wild Animals I Have Known and 200 Drawings: Being the Personal Histories of Lobo, Silverspot, Raggylup, Bingo, The Spring Field Fox, The Pacing Mustang, Wully, and Redruff. New York: Charles Scribner’s.

1件のコメント

コメントは受け付けていません。