Hiroaki Teraoka

July 31st, 2022.

This is a reproduction of the PDF file I published on this blog on July 31st, 2022. The PDF file is difficult to read without downloading it. Thus, I reproduce the contents of the PDF file here. I had to change some minor parts because underlines, bar notations and foot notes are unavailable on Word Press.

You can read sections 1-7 from the below links.

8 Negation and V-to-T movement

8.1 introduction

When you make a negative sentence, you use a negative word not.

(74) (a) He will not use this PC.

(b) He should not eat this cake.

Modal auxiliary verbs such as will and should are merged in T positions. Main verbs such as use and eat are merged in V positions. (74) reveals that the negative word not precedes the VP and follows the T head. In other words, not is sandwiched between the T and VP.

We have analyzed verbal suffixes such as -s and -ed as merged in T positions. In declarative sentence, the verbal affix -es is lowered to the V position by affix hopping.

(75) He speaks Japanese.

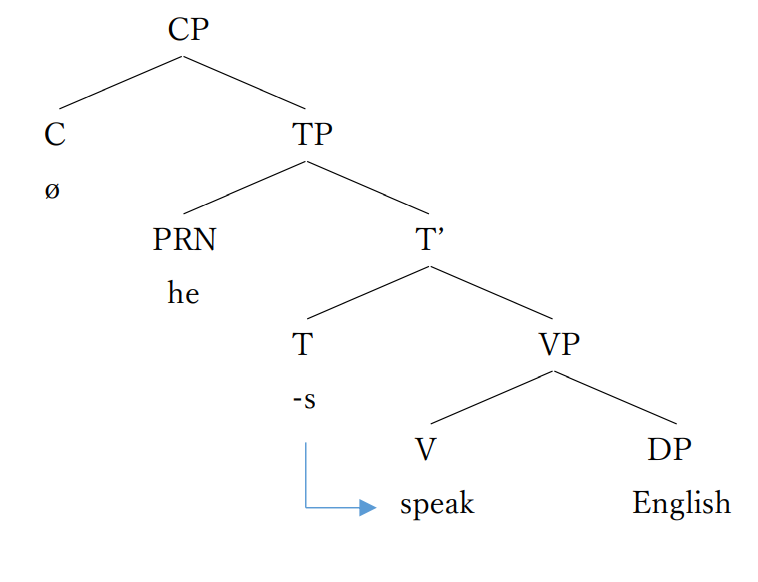

(76) The internal structure of (75)

Keep in mind that affix hopping is a phonological operation. The affix hopping works after the TP has merged with the phase head C and has been sent to the PF component to be assigned phonological representations. In other words, the affix hopping works in the PF component. Thus, syntactically, the verbal suffix remains in the T position. Supporting evidence comes from the yea-no question (or wh-question) and the negation of (75).

As I mentioned earlier, you make a yes-no question sentence by moving the constituent in the T to the C position. The head can only move to the adjacent head immediately c-commanding it. C is the next higher head above T. Thus, the constituent in T can move to C position. However, the constituent in V cannot pass over T in one movement.

(77) Does he speak English?

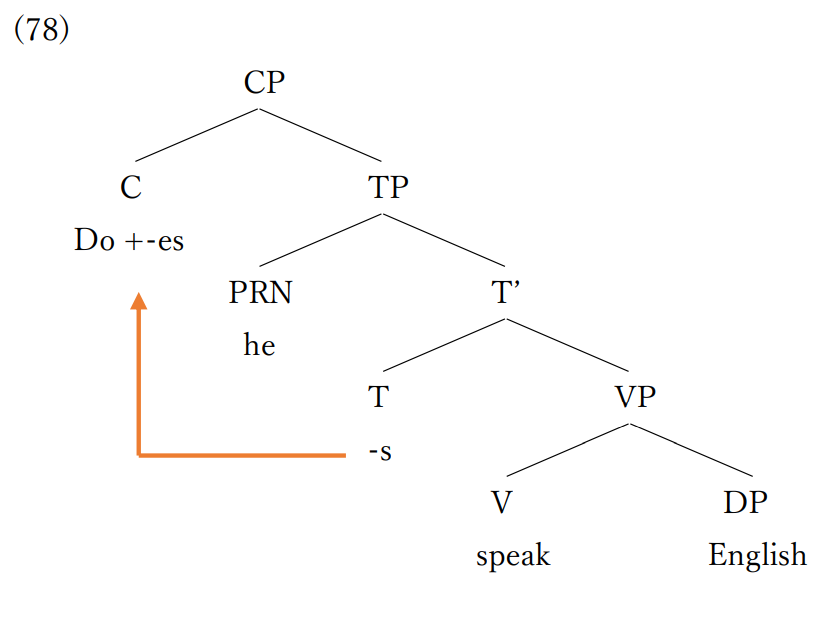

(77) shows that the verb remains in the V position and the verbal suffix in the T moves to the C position. The internal structure of (77) is as follows:

(78)

If the affix hopping were the syntactic operation, the result might be different. However, the verbal suffix remains in T, which is available to T-to-C movement. The moved verbal suffix needs a verbal host to be appropriately pronounced. The main verb in the V position is not able to move to the C position because the constituent in the V cannot jump over another head, namely, the T in this case. Thus, we insert a semantically null auxiliary verb do to support the verbal suffix. Linguists call this operation do support.

In a negative sentence, it seems that affix hopping cannot lower the verbal suffix in the T to the V position.

(79) He does not speak English.

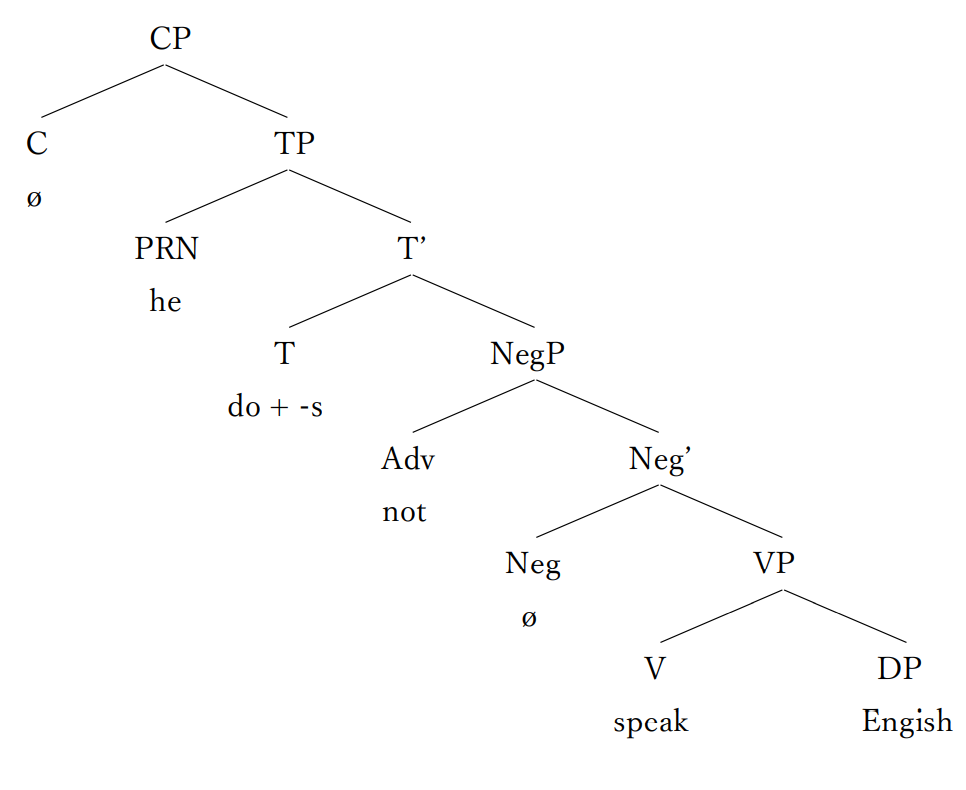

As we have seen above, not is sandwiched between the T and the VP. In a negative sentence, the verbal suffix remains in its original position, the T. The reasonable question is why the verbal suffixes originated in Ts cannot lower to the Vs in negations. Radford (2016) introduces negative phrases and solves this problem.

8.2 Negative Phrases (NegPs)

Radford (2016) proposes that a negative sentence in English has a negative phrase. He supposes that in present-day English, a negative phrase has a null constituent ø as its head and the negative word not as is specifier. Since a negative phrase is sandwiched between the T and VP, the internal structure of (79) is analyzed as (80).

(80)

Since a head can only move to the immediately higher or lower head, the verbal tense suffix in the T head cannot pass over the head of the negative phrase. Thus, affix hopping cannot move the verbal suffix in the T to the host verb in the V position. In this case, we insert a semantically null auxiliary verb do to rescue the verbal suffix stranded in the T position. Linguist call this operation do-support.

Negative phrase analysis reveals interesting points. Older English such as Early Modern English (which was spoken from 1500 to 1700) did not use affix hopping.

(81) (a) He loves not you (Shakespeare, Lysander, Midsummer Night’s Dream, III. ii [Quoted by Radford (2016: 314)])

(b) Speakest thou in sober meaning? (Shakespeare, Orlando, As You Like It, V. ii [Quoted by Radfrod (2016: 271)]) ‘Do you speak in sober meaning?’

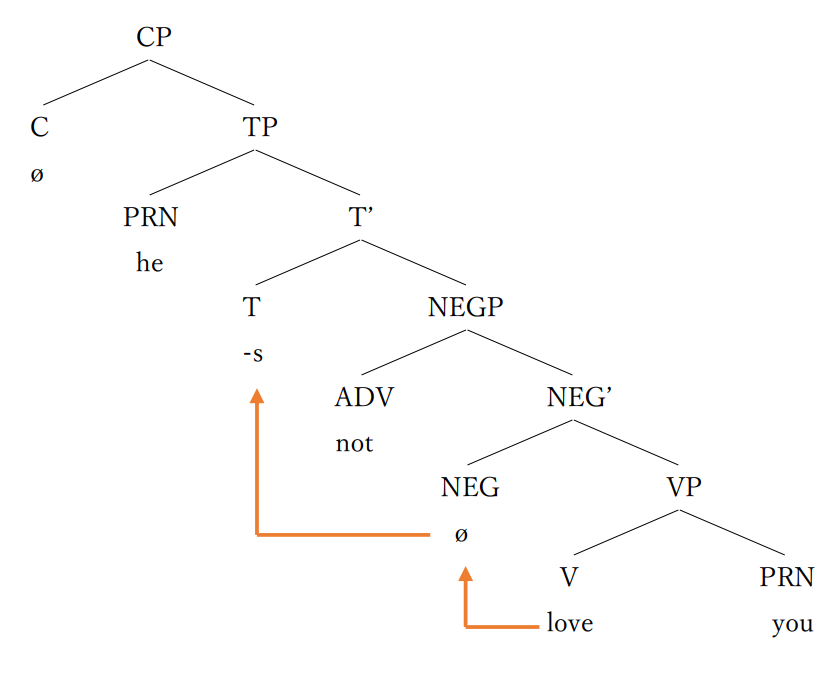

In (81a), the main verb precedes not. The main verb love generated in the V position moves through the head of the negative phrase to the T position. The tree diagram in (82) shows the internal structure of (81).

(82)

Second important thing about examples in (81) is that in (81b), the main verb precedes the subject thou in the specifier of the TP to make a yes-no question. This means that the verb generated in the V position moved upward to the T position and then moved to the C position with the verbal suffix. Thus, in Early Modern English, a verbal suffix in the T position attracted the movement of a verb generated in the V position (Roberts 2021). Thus, affix hopping did not happen at that time. The affix remained in its original position and the verb moved to the T position. Roberts (2007, 2021) calls this movement V-to-T movement. The constituents in a T position can move to the C position to form a question sentence. Thus, the verb in the T position moved to the C position with the suffix. Head movement cannot strand any constituents (Radford 2016).

According to Roberts (2021) whether a language adopts V-to-T movement (like in Early Modern English) or affix hopping (like in present-day English) depends on a parameter. The name of the parameter is unclear. I call this parameter the strong T parameter. A language with the positive value for the strong T parameter has morphologically rich verbal suffix. Early Modern English had four different verbal suffixes to distinguish subjects with different person-number features. These strong verbal suffixes in T attracted the movements of verbs. Present-day Italy and French have the positive values for the strong T parameter. Thus, in these languages, verbs move to the T positions. In contrast to Early Modern English, present day English has only two verbal suffixes in present tense, namely, -s and zero. These weak suffixes are lowered to the V positions when pronounced.

Negative phrase analysis shed light on another phenomenon. Middle English (which was spoken from around 1100 to 1500) had a negative concord. In the negative concord, one negative sentence has two negative words. As an example of Middle English, I cite a sentence from Chancer’s Wife of Bath’s Tale.

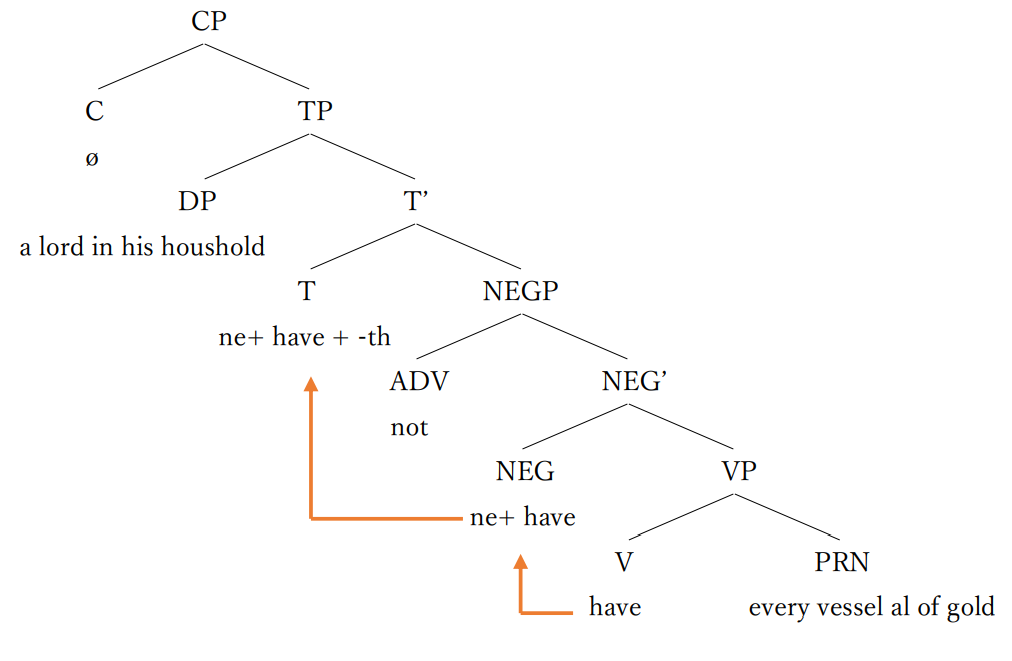

(83) A lord in his houshold ne hath nat every vessel al of gold

‘A lord in his household does not have all his vessels made entirely of gold’

(Chaucer, Wife of Bath’s Tale. [Quoted by Radford (2016: 285) emphasis original])

Radford (2016) analyzes the sentence in (83) as follows.

(84) The internal structure of (83)

Every vessel al of gold is a quantifier phrase (QP). Every and all are categorized as quantifiers. In this case, a quantifier every merges with a NP vessel al of gold to form the QP. We merge this QP with a V have to form a VP have every vessel of al of gold. We merge the resulting VP with the head of a negative phrase, ne. Note that the negative phrase in Middle English had ne as its head and not as its specifier. Middle English had the positive value for the V-to-T movement parameter (the strong T parameter). Thus, the constituent in the V need to move through the negative head to the T. When the negative head and the VP merges, have in the V moves out of the VP to the negative head. We merge the specifier of the negative phrase and get the full negative phrase. Then, we merge this negative phrase with the T -th to form the T-bar. This verbal suffix -th was strong and attracts the constituents in the negative head (or the constituent in V in a declarative clause). Thus, the constituents in the negative head moves to the T position. In head movements, we cannot strand anything. Ne and have in the head of the negative phrase move together to the T position. In this fashion, we get a string ne+ have+ -th in the T position. We merge DP a lord in his household as the specifier of the TP. When we pronounce this sentence, we spell out the string ne+ have+ -th in the T as ne has. In this way, we get a negative concord.

References)

Ando, S. (2005) Gendai Eibunnpou Kougi [Lectures on Modern English Grammar]. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Brinton, L. J and Arnovick L. K. (2017) The English Language – A linguistic History. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bybee, J. (2010) Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1955/1975) The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory. New York: Plenum.

Chomsky, N. (1957) Syntactic Structures. Leiden: Mouton & Co.

Chomsky, N. (1980) “On Binding.” Linguistic Inquiry. Vol. 11. No.1. Winter, 1980. pp. 1-46.

Chomsky, N. (1981) Lectures on Government and Binding – The Pisa Lecture. Hague: Mouton de Gruyter. (origionally published by Foris Publications)

Chomsky, N. (1986) Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995) The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1998) Minimalist Inquiries: The Framework, in Martin, R., Michhaels, D. and Uriagereka, J. (eds.) (2000) Step by Step, Essays on Minimalism in Honor of Howard Lasnik. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2001) “Derivation by Phrase.” In M. Kenstowics, ed., Ken Hale: A life in language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1-52.

Chomsky, N. (2004) “Beyond Explanatory Adaquacy.” In Belleti, A. ed. (2004) Structure and Beyond—The Cartography of Syntactic Structure. Vol.3. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, N. (2005) “Three Factors in Language Design.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 36, Number 1, Winter 2005: 1-22.

Chomsky, N. (2008) “On Phases.” In Freiden, R. Otero, C. P. and Zubizarreta, M. L. eds. (2008) Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory—Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 133-166.

Chomsky, N. (2021) Lecture by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going” Lecture at 161st meeting of Linguistic Society of Japan by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4F9NSVVVuw&t=4738s accessed on 13th May 2022.

Chomsky, N. and Lasnik, H. (1977) “Filters and Control.” Linguistic Inquiry 8: 425-504.

Cinque, G. (2020) The Syntax of Relative clause—A Unified Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donati, C. and Cecchetto, C. (2011) “Relabeling Heads: A Unified Account for Relativization Structures.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 42, Number 4, Fall 2011: 519-560.

Greenberg, G. H. (1963) “Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements”. In Denning, K. and Kemmer, S. (eds.) (1990) Selected Writing of Joseph H. Greenberg. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 40-70.

Inoue, K. (2006) “Case (with Special Reference to Japanese).” in in Everaert, M. and van van Riemsdijk, H.C. (eds.) The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. vol. 1, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 295-373.

Jackendoff, R. (1977) syntax—A Study of Phrase Structure. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Kegl, J., Senghas, A. and Coppola, M. (1999) “Creation through Contact: Sign Language Emergence and Sign Language Change in Nicaragua.” in DeGraff, M. (eds.) (1999) Language Creation and Language Change—Creolization, Diachrony, and Development. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 177-237.

Langacker, R. W. (1991) Foundation of Cognitive Grammar– Descriptive Application. Vol 2 Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Radford, A. (1988) Transformational Grammar – A First course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2004) Minimalist Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2009) Analyzing English Sentences – a Minimalist Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2016) Analyzing English Sentences. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rizzi, L. (2009) “Movements and Concepts of Locality.” in Piattelli-Palmarini, M., Uriagereka, J. and Salaburu, P. (eds.) (2009) Of Minds and Language—A Dialogue with Noam Chomsky in Basque Country. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, I. (2007) Diachronic Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, I. (2021) Diachronic Syntax. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sheehan, M., Biberauer, T., Roberts, I. and Holmberg, A. (2017) The Final-Over-Final Condition—A Syntactic University. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.