Hiroaki Teraoka

July 22th, 2022.

This is a reproduction of the contents of the PDF file I uploaded on this blog on July 22th, 2022. The PDF file is difficult to read without downloading it. Thus, I reproduce the contents of the PDF file here. I had to make some minor adjustment because underlines, footnotes and bar notations are unavailable on Word Press.

Sections 1-2 are available from the below link.

7 WH-Movement

7.1 Yes-No Questions

Before we see how wh-questions sentences are made, we should check the mechanisms of English yes-no question sentences.

(39) He will use this PC.

(40) Will he use this PC?

Traditional grammarians claim that we make yes-no question sentences by inverting the subject and the auxiliary verb. However, generative grammarians see the things differently.

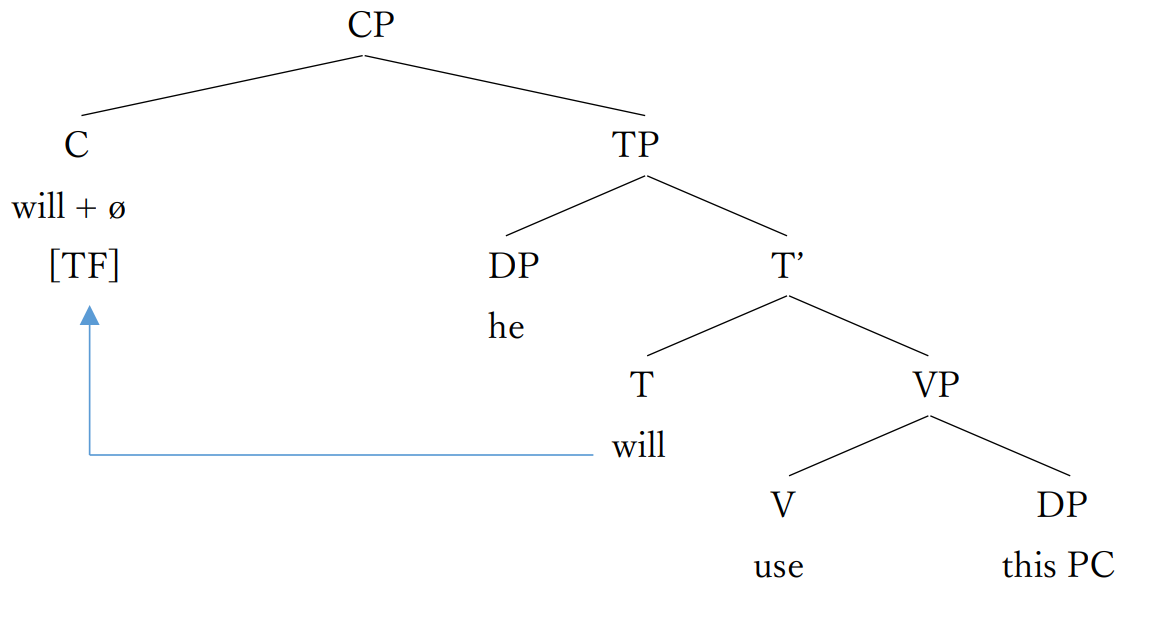

When we have generated the TP he will use this PC, we merge this TP with a yes-no question null C. The yes-no question null C is different form the declarative null C in that the yes-no question null C has the T feature. The T feature of the null C attracts the constituent in T to the edge of the CP. (The edge of the CP means the head and specifier of the CP.) Thus, the T feature of the null C attracts will in the head T position to the head C position as shown below:

(41) The internal structure of (40) will he use this PC?

In (41), we have made a yes-no question sentence by moving an auxiliary verb, which is positioned in T, to the head C position. However, how do you make a yes-no question sentence from a sentence without any auxiliary verbs like (42) below?

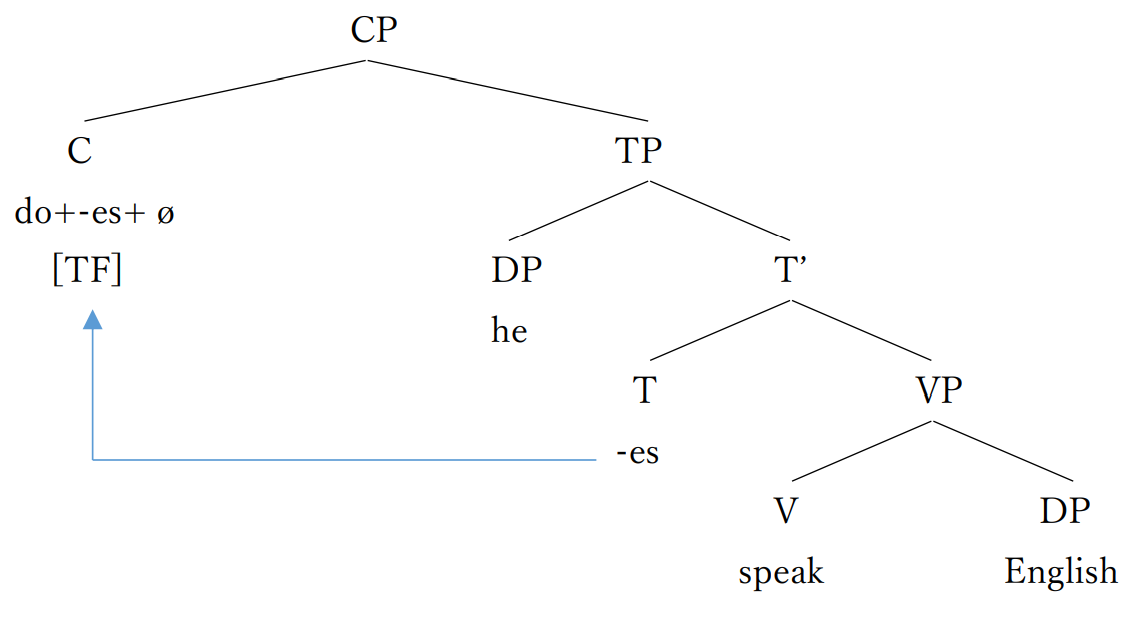

(42) He speaks English.

The sentence in (42) lacks an auxiliary verb. However, as the tree diagram in (43) shows, (42) has suffix –es in the T position. To make a question sentence, we move the constituent in the T position to the C position as shown in the tree diagram (43).

(43) The internal structure of the yes-no question sentence of (42) he speaks English.

The suffix –es left behind in the original T position is the copy of the moved suffix. Since a copy is phonologically deleted when the sentence is pronounced, the copy in the T position is silenced when pronounced. Real concern here is how to pronounce the moved suffix in the C position. The verbal suffix –es must be pronounced with verbal host. In present-day English, we insert an semantically null auxiliary do to the C position to save the verbal suffix –es. Thus, we get the sentence in (44). Linguists call this phenomenon of do-insertion do-support (Radford 2016).

(44) Does he speak English?

Note that regardless of the existence of the auxiliary verbs such as will and can, we have made the yes-no question sentences by moving the constituents in Ts to Cs. This T-to-C movement operations support the validity of affix hopping. Affix hopping is a phonological operation (see section 7.3 for phase theory and phonological operations). Syntactically, the verbal suffixes remain in their original positions (i.e. in Ts). If the verbal suffix has already gone to the V position, the result of T-to-C movement operation in (43) must have been different. (We see the different result in section 10 Negatives and V-to-T movements.)

You may have already noticed that a head can only move to the head immediately above it. This means that a head cannot jump over another head. Thus, only constituents in Ts can move to Cs. Constituents in Vs cannot move to Cs in one-go.

7.2 Wh-questions

The derivations of wh-movement question partially follow those of yes-no questions.

(45) He will use this PC.

(46) Will he use this PC?

(47) What will he use?

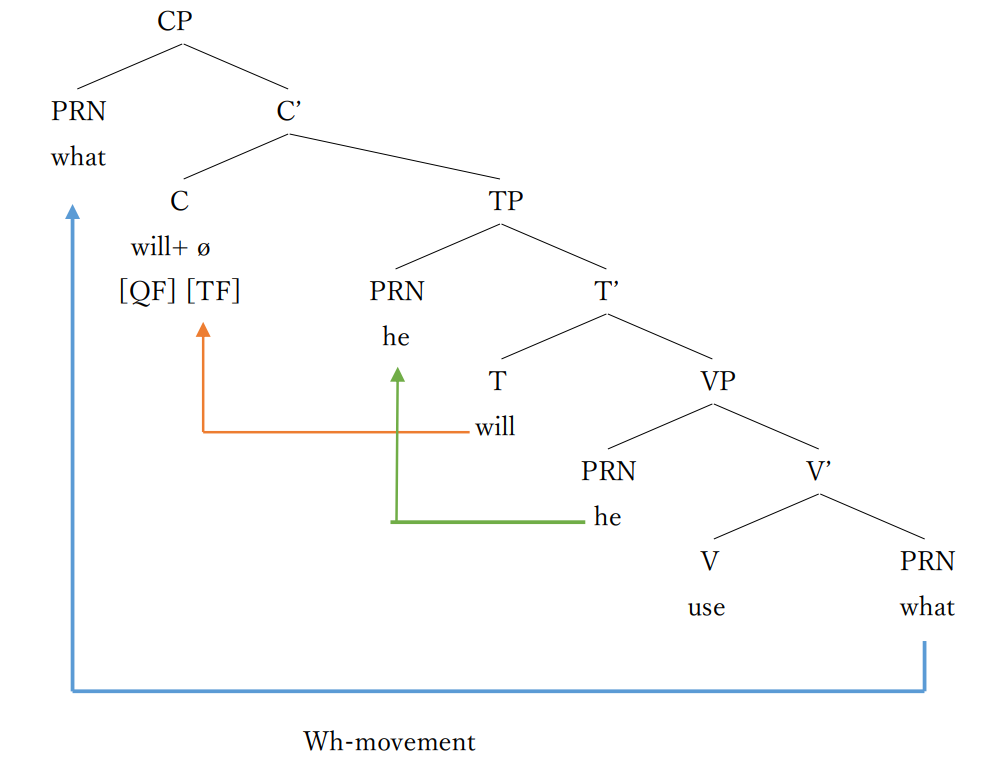

(48) The internal structure of (47).

As the above tree diagram shows, we merge the V use and wh pronoun what to form the V-bar use what. The pronoun what receives its theta-role of THEME from the c-commanding verb use. The pronoun he merges with this V-bar as the specifier of the VP. The pronoun he receives its theta-role of AGENT form the V-bar use what. We merge this VP with the T will to form the T-bar will use what. At the moment the T merges with its complement, the EPP feature of the T attracts the pronoun he in the specifier of the VP to the specifier of the TP. In this way, we get the whole TP. Then, we merge the resulting TP with the null wh-question C ø. This wh-question null C is different from the yes-no question null C in that the null C for wh-questions has both the T feature and Q feature. At the same time the wh-question null C merges with the TP, the T feature of the C attracts the constituent in T to the edge of the CP. Thus, will in the T position moves to the C position. The Q feature of the C attracts smallest maximal projection which contains a wh-phrase. In this case, question pronoun what itself is a maximal projection because it is a complement. Radford (1988) argue that only maximal projections (i.e. full phrases) can be complements. Thus, the Q feature of C attracts what to the edge of the CP. The landing site of what is the specifier of CP because what is not a head.

7.3 Successive wh-movements and phase theory

We have seen how a wh-phrase moves from its original position to the spec-CP. In this section, we see how we make a wh-question sentence like (49).

(49) What do you think (that) he stole?

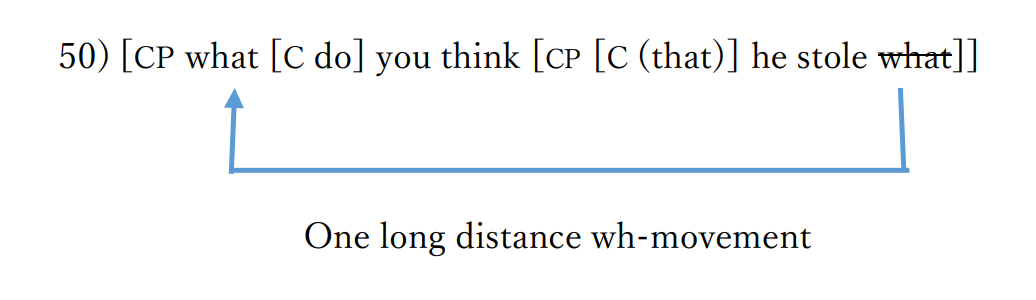

(49) is different from (48) in that the wh-question word what is moved from inside the embedded clause to the initial position of the main clause. You may wonder one long distance movement suffices.

However, the long distance movement like (50) is banned because there is a following condition:

(51) Impenetrability Condition

“A constituent c-commanded by a complementiser C is impenetrable to (so cannot agree with, or case-marked by, or be attracted by etc.) any constituent c-commanding the CP headed by C.” (Radford 2016: 356)

In (50), the lower TP he stole what is c-commanded by the lower C (that). The impenetrability condition (51) tells us that a constituent in the lower TP can move as far as the specifier of the lower CP. This means that the wh-question pronoun what cannot move to the specifier of the higher CP in one long distance movement.

You may wonder why the impenetrability condition (51) exists. The answer comes from Chomsky’s phase theory. Chomsky (1998, 2001, 2004, 2008) put forward an insightful idea. According to Chomsky, our working memory is so small that we do not retain a full sentence in our memory when we are making it. First, we make a part of a sentence and when that part is complete, we send it to the phonological component (PF component) ‘to be assigned appropriate phonetic representation’ (Radford 2009: 380). This small part of a sentence is called ‘a phase.’ Once the first phase is complete, we move on to the next phase. When we are building the second phase, the first phase is already in the PF. Thus, the first phase is no longer accessible to further syntactic operations.

Chomsky (2001, 2004, 2008) claims that CP and v*P are phases. We do not use v*P analysis here, so we can forget about v*Ps. Following Chomsky’s phase theory, we make the sentence in (49) repeated here as (52)

(52) What do you think (that) he stole?

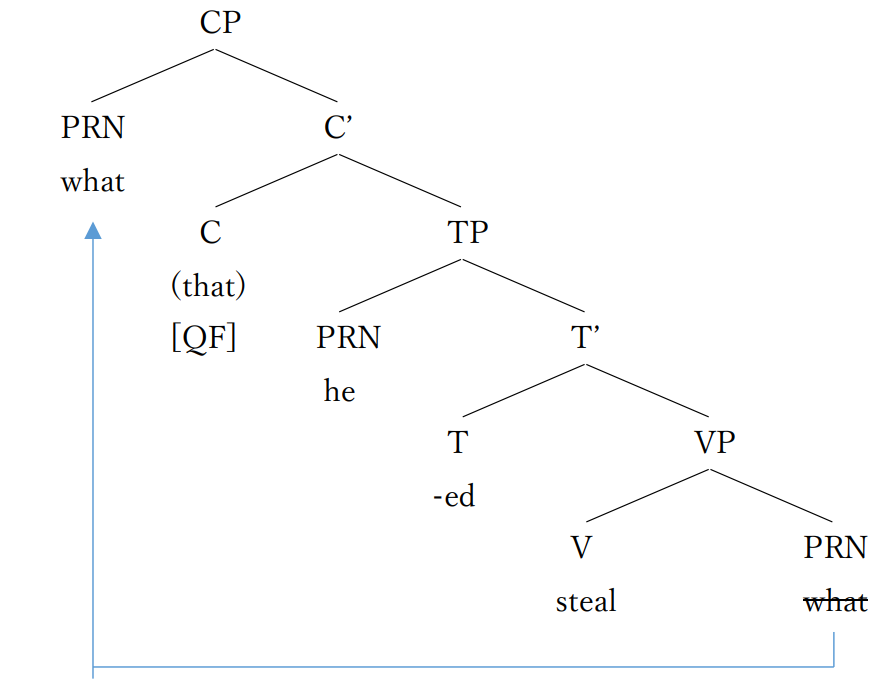

First, we make a TP he –ed steal what by successive mergers as the following tree diagram (54) shows. (Merger is a noun for merge.) Then, we merge this TP with a C that. According to Chomsky, C is a phase head. Thus, when we merge the C that with the TP, two things happen: first, all the syntactic operations concerning C are executed; second, the domain of the C (i.e. the complement of the C, namely, the TP) is sent to the phonological component (PF component).

(53) The internal structure of the first phase

The C that has a question feature (QF). This Q-feature attracts the wh-question phrase what to the specifier of the CP. After this wh-movement has been executed, the domain of the C (i.e. the TP) is sent to the phonological and semantic component. When the TP has been sent to phonological component, the TP is inaccessible to further syntactic operations. This means that we cannot extract any constituents out of the TP or constituents inside the TP cannot agree with constituents outside the relevant TP. This leads to the Impenetrability Condition (51). Chomsky (2001) put forward the following Phase Impenetrability Condition:

(54) The Phase-Impenetrability Condition (PIC)

“The domain of H is not accessible to operations outside HP; only H and its edge are accessible to such operations.” (Chomsky 2001: 13)

(H stands for a phase Head.)

This condition summarizes what has happened here. This phase impenetrability condition is similar to the Impenetrability Condition (51). When you replace H in (53) with C, you have a very similar condition to impenetrability condition (51). In fact, impenetrability condition (51) derives from the phase impenetrability condition (54).

When the TP he –ed steal what is sent to the phonological component, the copy of what at the extraction site is phonologically deleted. Also, the verbal suffix -ed is lowered to the V by affix hopping in the phonological component. Thus, affix hopping is phonological operation, not a syntactic one. In other words, syntactically, the verbal suffix -ed remains in the T. Section 7.1 (yes-no question) supports this idea. If syntactic operations have lowered verbal suffixes such as -es and -ed, the Cs cannot attract verbal suffixes.

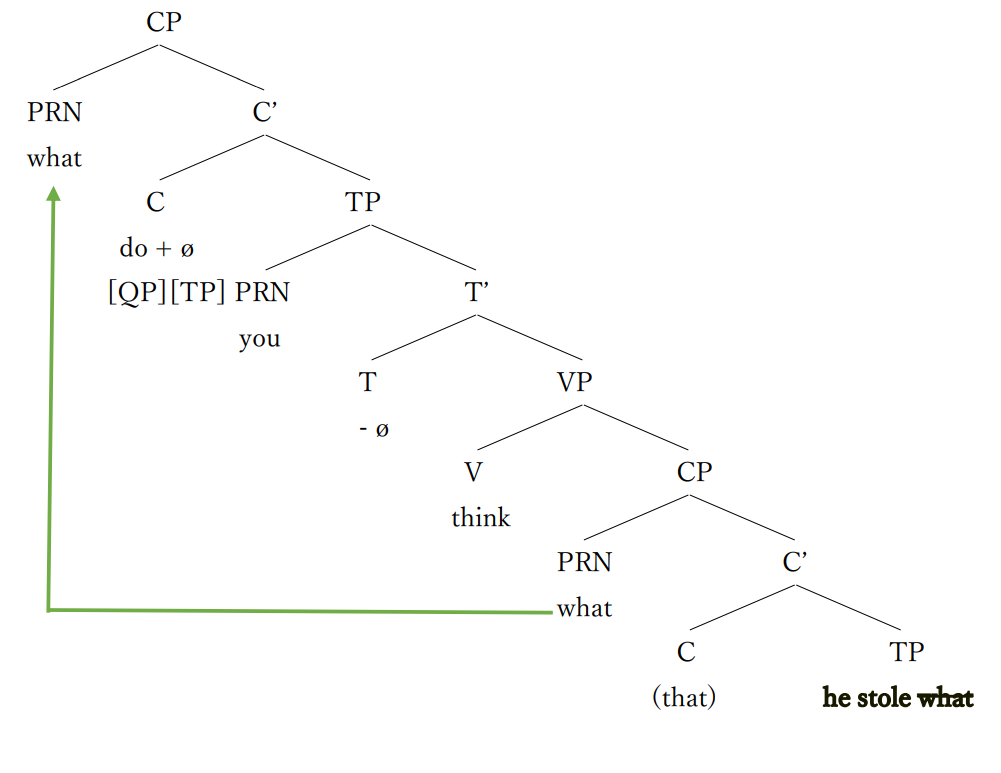

After we made the CP what he stole what in (54), we move on to the next phase. We merge this CP with a V think. By successive mergers, we get a whole TP as the below tree diagram (55) shows.

(55) The internal structure of the second phase.

We merge the resulting TP with a null wh-question C. This wh-question C has both the T feature and the Q-feature. The T-feature of the C search its domain (i.e. the TP) for a suitable candidate. Keep in mind that the lower TP c-commanded by the lower C that is already sent to the phonological component (PF component). Thus, we cannot extract anything from the lower TP. In other words, the lower TP is ‘frozen.’ I use the bold font to indicate that the TP is already gone to the PF. To borrow the words from Chomsky (2005, 2008), we ‘forget’ the lower TP. Thus, the T feature of the higher C only finds the verbal suffix – ø in the higher T position. The T feature of the higher C attracts this null verbal suffix to the higher C position. The Q-feature of the C attracts the smallest maximal projection containing a wh-question phrase. The lower TP is already sent to the PF component. We cannot extract anything out from the lower TP, so we move what in the specifier of the lower CP to the specifier of the higher CP.

After all the syntactic operations concerning the higher C have finished, the domain of the higher C (i.e. the higher TP) is sent to the phonological component. This is the second phase. You may wonder how we pronounce the specifier and the head of the highest CP—namely, what and do. We have two options. First option is as follows: we suppose that the specifier and the head of the highest CP are always sent to the phonological component regardless of phase theory. Second option is that we adopt Luigi Rizzi’s split C hypothesis and suppose that there is a higher C which takes the CP what do you think (that) he stole as its complement. This highest C is never pronounced in a root clause. (This explains why English does not have overt declarative null C that in a root clause.)

Summarizing, a wh-phrase generated in a lower TP is moved successively to the specifier of the highest CP. A sentence with n clauses moves a wh-phrase n times. In each movement, the wh-phrase in a TP moves to the specifier of the CP which takes that TP as its complement. This means that wh-phrases moves thorough specifiers of lower CPs.

A piece of evidence which supports this argument comes from floating quantifiers.

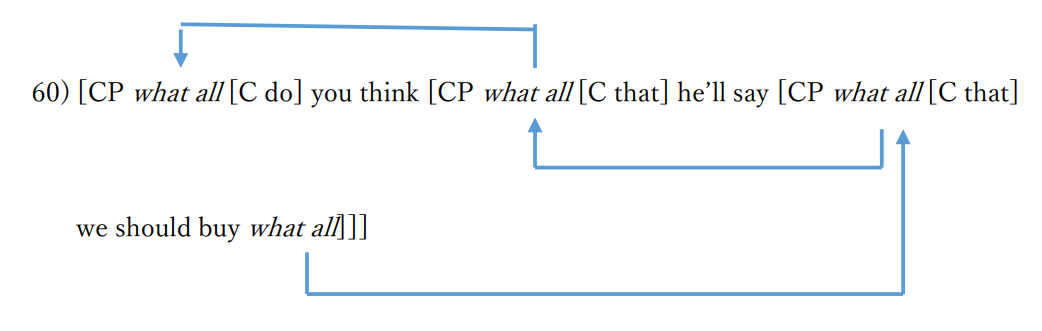

(56) What all do you think that he’ll say that we should buy?[2] (Radford 2009: 211)

(57) What do you think all that he’ll say that we should buy? (ibid.)

(58) What do you think that he’ll say all that we should buy? (ibid.)

(59) What do you think that he’ll say that we should buy all? (ibid.)

All in (57-59) are called floating quantifiers. Originally, what and all are generated like what all in (56). As the question phrase what all moves each time, the phrase leaves a copy of itself in its extraction site. The internal structure of (56-59) is as follows.

When you partially spell out italicized constituents, you get floating quantifier like (57-59).

Radford (2009) also reports the following examples.

(61) You think they went how far inside the tunnel?[3] (Radford 2009: 210)

(62) How far inside the tunnel do you think they went? (ibid.)

(63) % How far do you think inside the tunnel they went? (ibid.)

The mechanisms behind (61-63) are almost the same as the floating quantifiers. How far inside the tunnel is a preposition phrase (PP) which has a preposition inside as its head.

(64) [PP how far [P inside] the tunnel]

The internal structure of (61-63) are as follows:

(65) [CP how far inside the tunnel [C do] you think [CP how far inside the tunnel [C ø] they went how far inside the tunnel]]]

(65) has two movement operation, the first operation moves the PP in the lower TP to the specifier of the lower CP. The second movement operation moves the PP in the specifier of the lower CP to the specifier of the higher CP. Each time the PP is moved, the PP leaves a copy of itself in its excavation site. By partially spelling out the copies, we get (63).

7.4 Relative Clauses.

We can make relative clauses by wh-movements (Chomsky 1981) .

(66) a. The book [which John wrote] sells well.

b. The book [that John wrote] sells well.

c. The book [ø John wrote] sells well.

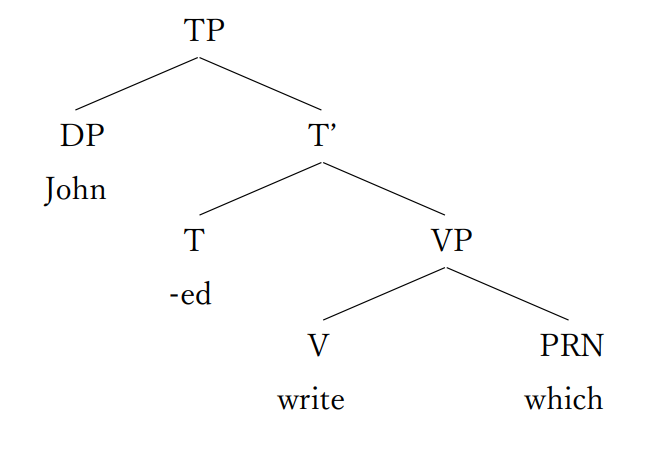

I make the sentence(s) in (66) to show how relative clause constructions are made by wh-movement approaches.

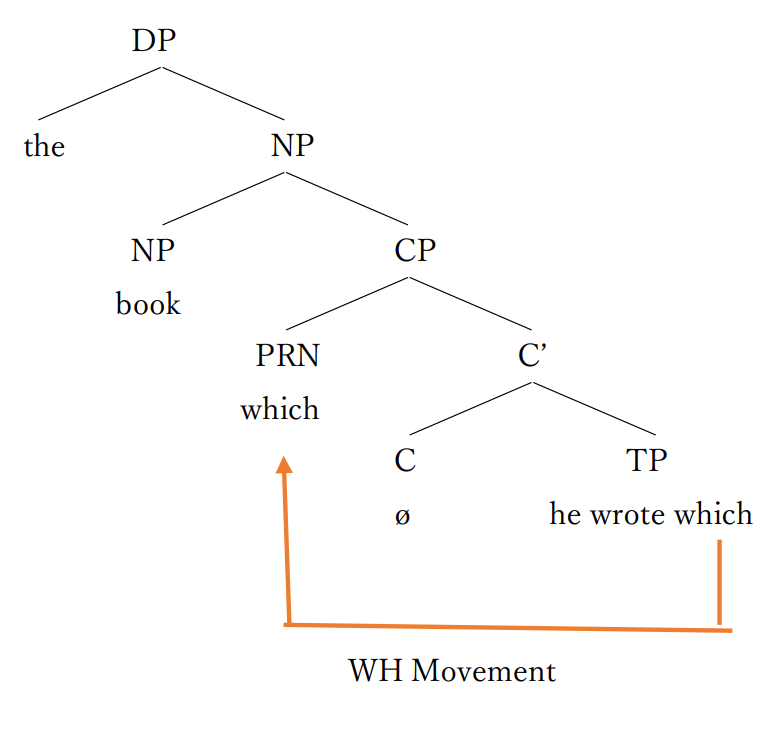

(67)

We merge the V write and a relative pronoun which to form the VP write which. The relative pronoun which receives the theta-role of THEME from the c-commanding V write. (In other words, the V write assigns the theta-role of THEME to its sister, namely, the relative pronoun which.) To simplify things, I ignore the VP Internal Subject Hypothesis here. We make the whole TP by successive mergers.

We merge the resulting TP with a null C ø. This null C is for a relative clause. This null C has a wh-feature but does not have a T-feature. Thus, this null C attracts the smallest maximal projection which contains a wh-word to the edge of the CP. (Recall that the edge of a phrase is the head and the specifier of the phrase.)

(68)

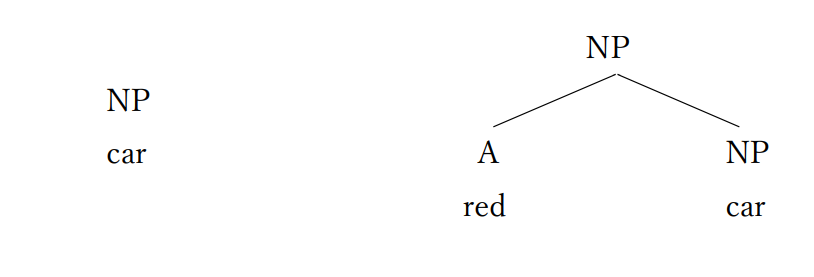

In this example, the null C attracts the relative pronoun which to the edge of the CP. The landing site of the relative pronoun which is the specifier of the CP because only head can be moved to another head position. The relative pronoun which is not a head because it is merged as the complement of the V. Usually, complements are not heads. Thus, the relative pronoun keeps its original theta-role and moves to the specifier of the CP position. Thus far, we have made a CP which ø he wrote which. We merge this CP with a NP book. This time, the whole CP is treated as an adjunct. An adjunct is the fourth category generative grammarians use. (We have already seen heads, complements and specifiers.) An adjunct merges with a constituent and makes that constituent even larger. Adjuncts do not change the grammatical categories of the constituents they merge with. For example, NP car do not change its grammatical category even after we have merged an adjunct red with the NP car.

(69)

Merging an adjective (A) red with NP car gives us an even larger NP red car. Similar thing happens in (68). In (68), the CP merges with a NP book as an adjunct and makes this NP even larger. We merge this large NP book which ø he wrote which with the determiner the to form the DP the book which ø he wrote which. In PF component, the copy of the relative pronoun which in the original position is phonologically delete. The verbal suffix -ed is lowered to the V by affix hopping.

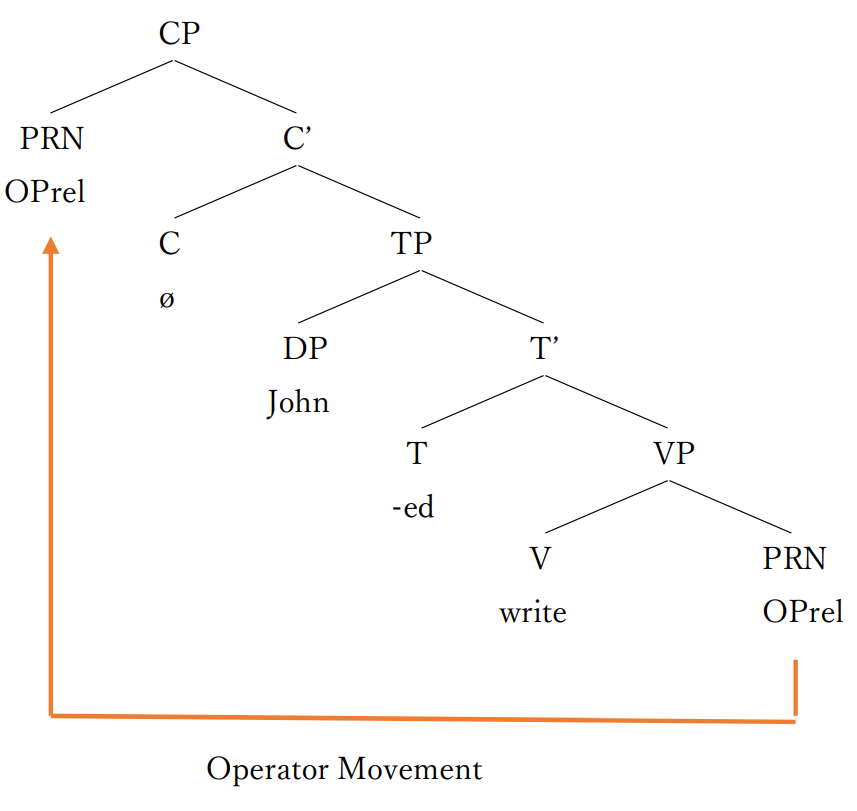

We can make (66c) in the following fashion. We merge the V write and a null relative operator OPrel to form the VP write OPrel. This null operator for a relative clause receives its theta-role THEME from the c-commanding V write. After we have made the C-bar ø John -ed write OPrel, we move the null operator to the specifier of the CP position. Keep in mind that the relative operator holds its theta-role THEME. By this operator movement, we get the full CP as the below tree diagram shows.

(70)

After all the syntactic operation concerning the null C has finished, the domain of the phase head C (i.e. the TP) is sent to the PF component to be assigned phonological representation. In the PF, the verbal suffix -ed is lowered to the V by the operation affix hopping. We merge this CP with a NP book to form an even larger NP book OPrel John -ed write OPrel. We merge this larger NP with the determiner the to form the example in (66c) the book [ø John wrote] sells well.

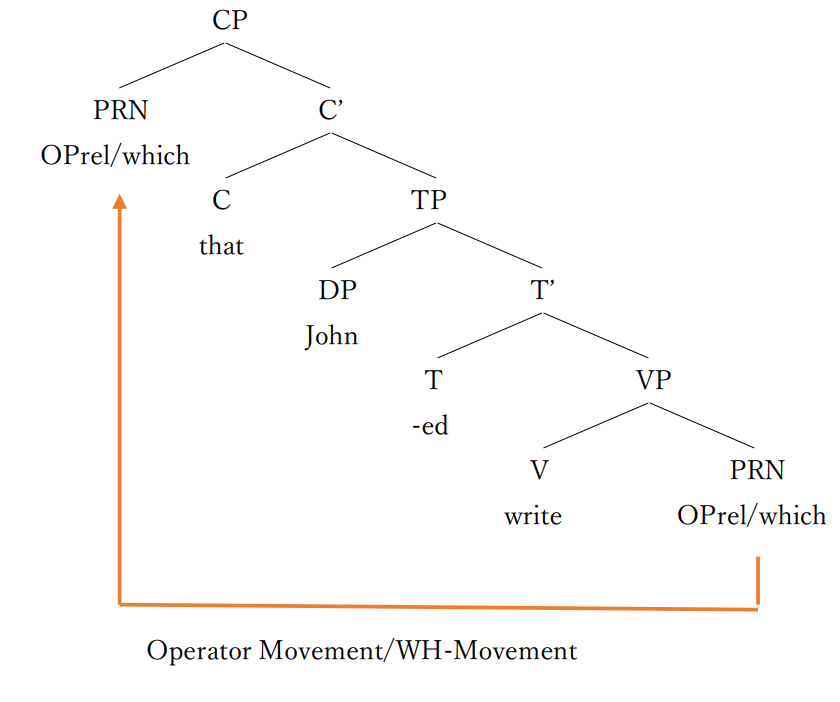

Thus far, we have used null complementizers (Cs) for the head of the CPs. When we use an overt complementizer that instead of the null complementizer, we get the below constructions.

(71)

(72) a. The book [CP which [C that] John wrote] sells well.

b. The book [CP [C that] John wrote] sells well.

When we use the relative pronoun which, we get (72a). When we use the null relative operator OPrel instead of the overt relative pronoun which, we get (72b). (72a) is ungrammatical in present-day English. However, similar construction was grammatical in older English such as Middle English (which was spoken from 1100 to 1500).

(73) Only the sight of hire, whom that I serve,… (Chaucer, Knight’s Tale 1231: line 373; from Cinque 2020: 53)

A question arises here: why the constructions such as (72a) and (73) are ungrammatical in present-day English. Chomsky and Lasnik (1977) tried to answer this question. They thought up of the concept of the Doubly Filled Comp Filter (DFCF). They supposed that present-day English has the DFCF, which works in PF component (where phonological representation is assigned to the phrase already made). Simply put, this DFCF phonologically filters out structures such as (73) as ill formed.

(73) * [CP wh- [C that] ]

(73) shows a construction in which a CP has overt head and specifier. Chomsky and Lasnik claim that when a CP has overt head and specifier, we phonologically delete at least either the specifier or the head of the CP. This DFCF has descriptive power but it does not have an explanatory power. In other words, Chomsky and Lasnik (1977) did not explain why (72a) is ungrammatical in present-day English. They just described the facts.

[1] Only maximal projections (i.e. full phrase) can be used as complement (Radford 1988). Also see (9) above.

[2] An English native speaker informant comments that (56)-(59) are anacceptable.

[3] An English native speaker informant comments that he do not use (61).

This is the end of this blog post. You can access the next section from the below link.

References)

Ando, S. (2005) Gendai Eibunnpou Kougi [Lectures on Modern English Grammar]. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Brinton, L. J and Arnovick L. K. (2017) The English Language – A linguistic History. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bybee, J. (2010) Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1955/1975) The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory. New York: Plenum.

Chomsky, N. (1957) Syntactic Structures. Leiden: Mouton & Co.

Chomsky, N. (1980) “On Binding.” Linguistic Inquiry. Vol. 11. No.1. Winter, 1980. pp. 1-46.

Chomsky, N. (1981) Lectures on Government and Binding – The Pisa Lecture. Hague: Mouton de Gruyter. (origionally published by Foris Publications)

Chomsky, N. (1986) Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995) The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1998) Minimalist Inquiries: The Framework, in Martin, R., Michhaels, D. and Uriagereka, J. (eds.) (2000) Step by Step, Essays on Minimalism in Honor of Howard Lasnik. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2001) “Derivation by Phrase.” In M. Kenstowics, ed., Ken Hale: A life in language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1-52.

Chomsky, N. (2004) “Beyond Explanatory Adaquacy.” In Belleti, A. ed. (2004) Structure and Beyond—The Cartography of Syntactic Structure. Vol.3. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, N. (2005) “Three Factors in Language Design.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 36, Number 1, Winter 2005: 1-22.

Chomsky, N. (2008) “On Phases.” In Freiden, R. Otero, C. P. and Zubizarreta, M. L. eds. (2008) Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory—Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 133-166.

Chomsky, N. (2021) Lecture by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going” Lecture at 161st meeting of Linguistic Society of Japan by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4F9NSVVVuw&t=4738s accessed on 13th May 2022.

Chomsky, N. and Lasnik, H. (1977) “Filters and Control.” Linguistic Inquiry 8: 425-504.

Cinque, G. (2020) The Syntax of Relative clause—A Unified Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donati, C. and Cecchetto, C. (2011) “Relabeling Heads: A Unified Account for Relativization Structures.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 42, Number 4, Fall 2011: 519-560.

Greenberg, G. H. (1963) “Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements”. In Denning, K. and Kemmer, S. (eds.) (1990) Selected Writing of Joseph H. Greenberg. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 40-70.

Inoue, K. (2006) “Case (with Special Reference to Japanese).” in in Everaert, M. and van van Riemsdijk, H.C. (eds.) The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. vol. 1, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 295-373.

Jackendoff, R. (1977) syntax—A Study of Phrase Structure. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Kegl, J., Senghas, A. and Coppola, M. (1999) “Creation through Contact: Sign Language Emergence and Sign Language Change in Nicaragua.” in DeGraff, M. (eds.) (1999) Language Creation and Language Change—Creolization, Diachrony, and Development. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 177-237.

Langacker, R. W. (1991) Foundation of Cognitive Grammar– Descriptive Application. Vol 2 Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Radford, A. (1988) Transformational Grammar – A First course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2004) Minimalist Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2009) Analyzing English Sentences – a Minimalist Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2016) Analyzing English Sentences. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rizzi, L. (2009) “Movements and Concepts of Locality.” in Piattelli-Palmarini, M., Uriagereka, J. and Salaburu, P. (eds.) (2009) Of Minds and Language—A Dialogue with Noam Chomsky in Basque Country. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, I. (2007) Diachronic Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, I. (2021) Diachronic Syntax. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sheehan, M., Biberauer, T., Roberts, I. and Holmberg, A. (2017) The Final-Over-Final Condition—A Syntactic University. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Further Reading)

I am sure the most of the readers of this article are beginners of generative grammar. For beginners of generative grammar, I recommend books written by Andrew Radford. His explanation is very clear and easy to understand. Bibliography lists of his books are also useful for students. Radford (1988) is a bit old but is good as a starting point. Radford (2009) gives a thorough explanation about theta-roles and wh-movement. Radford (2016) does not elaborate on theta-roles but gives an insightful ideas about relative clause constructions.

For advanced students, I recommend Noam Chomsky’s books. Chomsky (1981) is a bit old but easy to understand compared to other books he wrote. Chomsky (1995) is the bible for generative grammarians. Although some analysis adopted in this book is out of fashion now, The Minimalist Program is the first book Chomsky put forward the idea of minimalist approach. Thus, those who aspire to be a researcher must read the book at least once.

For phase theories, you should consult Chomsky (2001. 2004, 2008). Especially, Chomsky (2001) is resourceful. This is the first book Chomsky put forward the idea of the Phase Impenetrability Condition. Chomsky (2004) and Chomsky (2008) refine the idea of phase.

1件のコメント

コメントは受け付けていません。