Hiroaki Teraoka

July 22th, 2022.

This is a reproduction of the PDF file I published on this blog on 22th July, 2022. The PDF file is difficult to read without downloading it. Thus, I reproduce the contents of the PDF file here for those who do not want to download the file. I had to change some minor parts because underlines and upper bars are unavailable on Word Press.

Sections 1-2 are available from the URL below.

Sections 3-4 are available from the below URL.

4 Theta-roles and the VP Internal Subject Hypothesis

4.1 arguments and theta-roles

Almost all sentences have predicates. A predicate expresses an activity or event. The activity and event expressed by predicates have participants. Linguist call these participants of activities or event arguments (Ando 2005, Radford 2004, 2009). Generative grammarians believe that every argument in a sentence has its theta-role. Theta-roles are semantic roles assigned to arguments. (I do not know the difference between theta-roles and semantic roles.)

(17) Tom killed Mary.

[AGENT] [THEME]

For example, the action of killing somebody needs two participants, namely the killer and the person (or a living thing) who is killed. These two participants are arguments of the activity of killing somebody. Thus, in (17), both Tom and Mary are arguments of the predicate. Linguists believe that every argument must have a theta-role. Tom is understood as the killer and Mary is interpreted as the person who is killed. Thus, Mary has the theta-role of THEME (i.e. a victim in this case). Tom has the theta-role of AGENT (i.e. the one who started the action). Different linguists accept slightly different theta-roles. Here, I adopt those of Andrew Radford’s (2009).

(18) A list of theta-roles and their meanings.

| Role | Gloss | Examples |

| THEME | Entity undergoing the effect of some action. | Mary fell over. |

| AGENT | Entity instigating some action. | Debbie killed Harry. |

| EXPERIENCER | Entity expressing some psychological state. | I like syntax |

| LOCATIVE | Place in which something is situated or takes place. | He hid it under the table. |

| GOAL | Entity representing the destination of some other entity. | John went home. |

| SOURSE | Entity from which something moves. | He returned from Paris. |

| INSTRUMENT | Means used to perform some action. | He hit it with a hammer. |

(Adapted from Radford 2009: 245-246)

We analyze proper nouns in argument positions such as Mary and Tom as DPs. NPs cannot refer to concrete entities but DPs can do so. Thus, Mary and Tom in (17) has null D ø as their heads. The internal structure of Mary in (17) is [DP ø [NP Mary]]. This analysis is supported by the fact that proper nouns in Greek has determiners such as o and tia in the following example:

(19) Greek

O Gianis thavmazi tin Maria.

The John admires the Mary. (= ‘John admires Mary’) (Radford 2016: 222)

A question arises how a DP receives its theta-role. If you rewrite (17) as Tom killed the elephant, the DP elephant following the verb kill still receives the theta-role of THEME. This means that theta-role assignments do not depend on DPs but depend on verbs. In the following section, we see mechanisms of theta-role assignments.

4.2 VP internal subject hypothesis

In order to understand mechanisms behind theta-role assignments, we need to get familiar with the concept of c-command. C-command stands for constituent command. C-command is the most important relationship between constituents (Chomsky 1995, Radford 2004, 2009, 2016).

(20) c-command

If a constituent A and B are sisters, A c-commands B and every constituent contained in B.

We check how c-command words in a real situation. We build the sentence (17). First, we merge a V kill with a DP Mary. The resulting phrase kill Mary is V-bar. Here, we depart from the analysis we adopted in section 5.

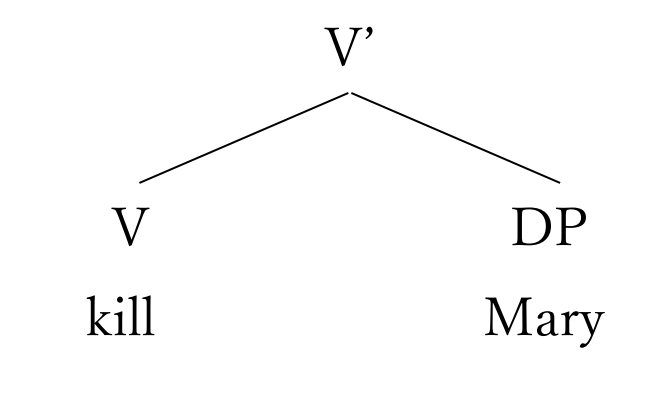

21) The internal structure of V-bar kill Mary.

The tree diagram (21) shows that the V kill and the DP Mary are sisters. By the definition of c-command (20), sisters c-command each other. Thus, the V kill c-commands the DP Mary. The DP Mary receives its theta-role of THEME from the c-commanding V kill. This means that the relation c-command plays a crucial role in theta-role assignments. In this case, the V kill assigns a theta-role THEME to the c-commanded constituent, the DP Mary. So-called objects are internal arguments of predicates. Thus, we can say that internal arguments receive its theta-roles from the c-commanding verbs.

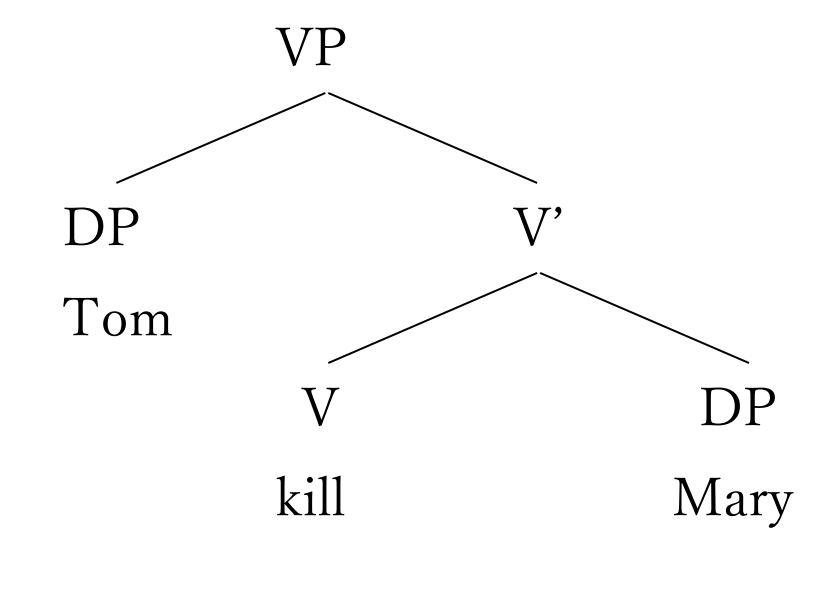

So-called subjects are external arguments of predicates. Things seem to be more complicated when you consider theta-role assignments of external arguments (i.e. subjects). Thus far, we have made the V-bar kill Mary. We merge this V-bar kill Mary with the DP Tom. DP Tom is the subject of the verb and it is merged as the specifier of the V. The resulting phrase is VP Tom kill Mary and the internal structure of the VP is shown in the tree diagram (20).

(22) The internal structure of the VP Tom kill Mary.

At first sight, the V kill seems to assign the theta-role of AGENT to the subject DP Tom. However, the V kill does not c-commands the subjects DP Tom but the V-bar kill Mary c-commands the subject DP Tom. V-bar kill Mary and the specifier of VP Tom are sisters. By definition of c-command (20), sisters c-command each other. We have already seen that c-command plays an important role in theta-role assignments. This means the V-bar as a whole assigns the theta-role of AGENT to the external argument Tom. Summarizing, an internal argument (i.e. an objects) receives its theta-role from the c-commanding V. On the other hand, external argument (i.e. a subject) receives its theta-role from the c-commanding V-bar as a whole.

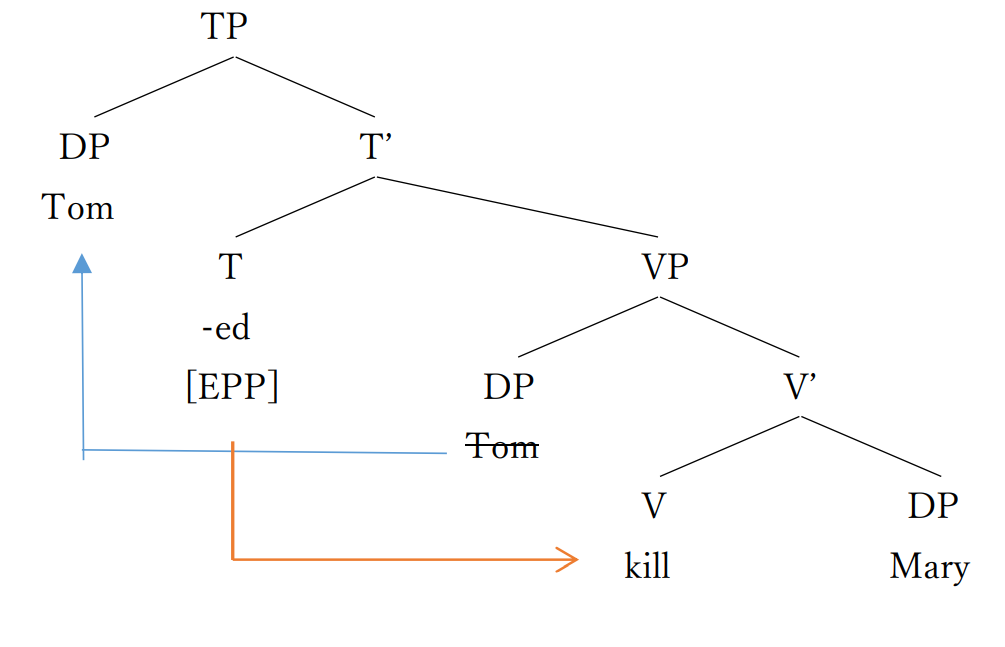

We merge a T suffix –ed with the VP Tom kill Mary to form the T-bar –ed Tom kill Mary. In English, all Ts have EPP features (Radford 2004, 2009). EPP stands for Extended Projection Principle. A head with the EPP feature must have a specifier. Thus, the T-ed search its domain for a suitable candidate. The domain of a head H is the complement of the head H. Thus, the T’s domain is its complement VP. (Every head c-commands its complement. C-commanding relation also plays an important role here.) The EPP feature of T acts like a probe. The EPP feature of the T search the VP for a suitable goal and when the EPP finds the goal, which is the DP Tom in the specifier of VP position, the EPP feature attracts the DP Tom to the edge of the TP. (Recall that the edge of a phrase is the specifier and the head of the phrase.) Chomsky (1981, 1995) put forward several constrains on movements. For example, a head can only move to another head position. There are no movements to complement positions. A constituent in a specifier position can move to another specifier position. Thus, the DP Tom in the specifier of the VP moves to the specifier of the TP position. In this fashion, we have made the whole TP Tom –ed Tom kill Mary. Chomsky (1995) claims that when a constituent moves, it leaves a copy of itself in its original position. In this case, the DP Tom in the specifier of the VP is the copy. The internal structure of the TP is shown in the tree diagram (23). When you pronounce the TP Tom –ed Tom kill Mary, two things happen. First, the copy is phonologically deleted. Second, the suffix -ed is lowered to the V position because the verbal suffix -ed must be pronounced with verbs. This lowering operation is called affix hopping (Chomsky 1957). Keep in mind that affix hopping is a phonological operation and that syntactically the tense affix -ed remains in the head T position (Radford 2009. 2016).

(23) The internal structure of the TP Tom -ed kill Mary.

An important thing about the TP in (23) is that the theta-role of the DP Tom does not change even after the DP Tom has been moved from inside the VP to the specifier of the TP. Once the DP Tom in the VP receives the theta-role of AGENT form the V-bar kill Mary, the DP Tom retains that theta-role and moves to the specifier of the TP position. According to Radford (1988), Ray Jackendoff put forward the idea of theta-role criteria. Radford (1988) explain about the theta-criteria. Once a constituent receives a theta-role, any operation including movements cannot change the theta-role of that constituent. Thus, the DP Tom in the specifier of TP has the same theta-role as its original VP internal position.

We have seen above how all the arguments of a verb are generated inside the VP. The internal argument (i.e. the object) of a verb receives its theta-role from the c-commanding verb. The external argument (i.e. the subject) receives its theta-role from the c-commanding V-bar, and moves to some higher position such as the specifier of TP. Linguists call this idea VP Internal Subject Hypothesis and most generative grammarians accept this hypothesis.

Evidence which seems to support the VP internal subject hypothesis comes from several phenomena. First of these phenomena is as follows:

(24) (a) John broke the window. (Radford 2009: 253)

(b) John broke his arm. (ibid.)

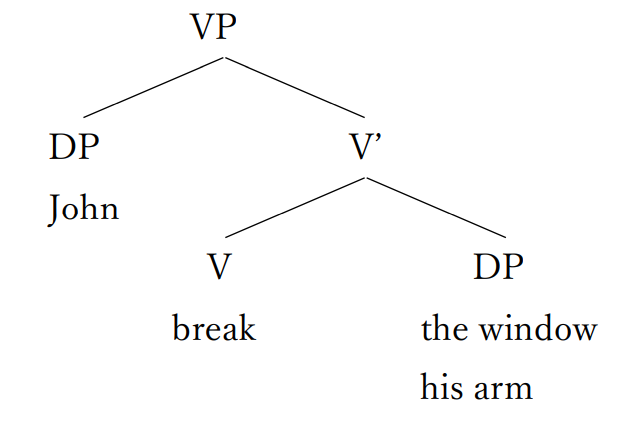

In (24), both the window and his arm have the same theta-role of THEME. Both the window and his arm are understood as things which are broken (i.e. victims). Both the window and his arm are c-commanded by the same V break. Thus, we can say that the V break assigns the theta role of THEME to the c-commanded DP. However, the DP John in (24a) and the DP John in (24b) seem to have different theta-roles despite the fact that both sentences have the same verb break. John in (24a) has the theta role of AGENT. An AGENT can start an action intentionally. On the other hand, John in (24b) has the theta-role of EXPERIENCER. An EXPERIENCER experience pain or some other psychological state. This phenomenon can be explained by adopting the VP Internal Subject Hypothesis. In (24a) the V break and the DP the window merge to form a unitary constituent V-bar break the window. The V-bat break the window as a whole assigns the theta-role of AGENT to the c-commanded DP John. In (24b), the V break and the DP his arm merge to form a unitary constituent, V-bar break his arm. This V-bar break his arm as a whole assigns the theta-role of EXPERIENCER to the c-commanded DP John.

(25) The internal structures of (24ab)

Another fact which supports the VP Internal Subject Hypothesis comes from floating quantifiers. The examples of floating quantifiers are as follows:

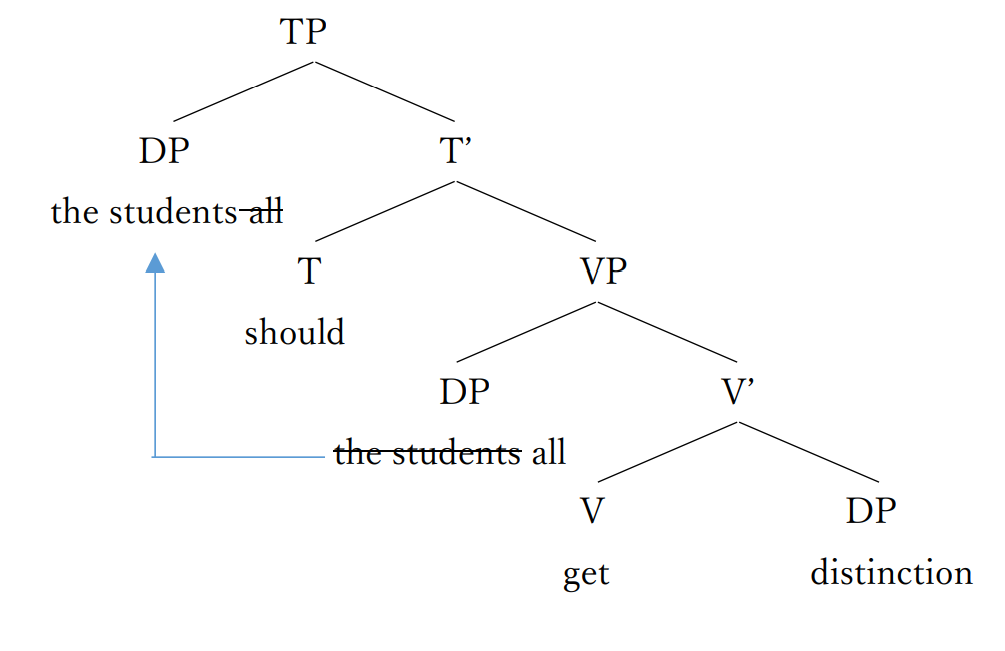

(26) The students should all/both/each get distinctions. (Radford 2009: 245)

(27) The students all/both/each should get distinctions. (ibid.)

all/ both/ each used like (26) are called floating quantifiers. They modify the DP the students. These quantifiers are separated from the DP the students but these quantifiers are understood to be modifying the DP. Why is this? The answer to this question is that the DP the students and the quantifiers all/ both/ each are originally generated together as a larger DP the students all/ both/ each and this larger DP is originally generated inside the VP. This larger DP is moved to the specifier of TP position as the tree diagram below shows.

(28) The internal structures of (26) and (27).

As I have already mentioned above, Chomsky (1995) claims that when a constituent moves, the moved constituent leaves a copy of itself in the original position. Usually, copies are phonetically deleted when pronounced like the case of (27). However, copies are sometimes partially spelled out. In the case of (28), we phonetically silence the quantifier all in the spec-TP position. On the other hand, we silence the student in the spec-VP position but overtly spell out the quantifier all in that position. In this way, we get an example in (26). Langacker (1991) argues that other that wh-question phrases, subjects are the sole elements which allow floating quantifiers. This means that objects do not usually accept floating quantifiers. Lagnecker’s claim supports the VP Internal Subject Hypothesis because under that hypothesis, objects do not move but subjects move from inside VPs to the spec-TPs. (See unaccusative section in Radford 2009 for cases where complements of Vs move to the spec-VPs.)

6 Passive

In this section, we see how passive sentences are made.

(29) Tom killed Mary.

[AGENT] [THEME]

(30) Mary was killed.

[THEME]

(30) is the passive of (29). (29) has two arguments but (30) has only one argument. According to Brinton and Arnovick (2017), passivization reduces the number of arguments a verb has. When you change a verb in the active voice to the passive voice, the number of arguments the verb has decreases by one. Thus, theoretically speaking you can passivize a verb which has two or three arguments in the active voice. On the other hand, you cannot passivize a verb which has only one argument in its active voice.

- He runs very fast.

- ??He is run. (Intended as the passive of 31)

(31) and (32) endorse our prediction.

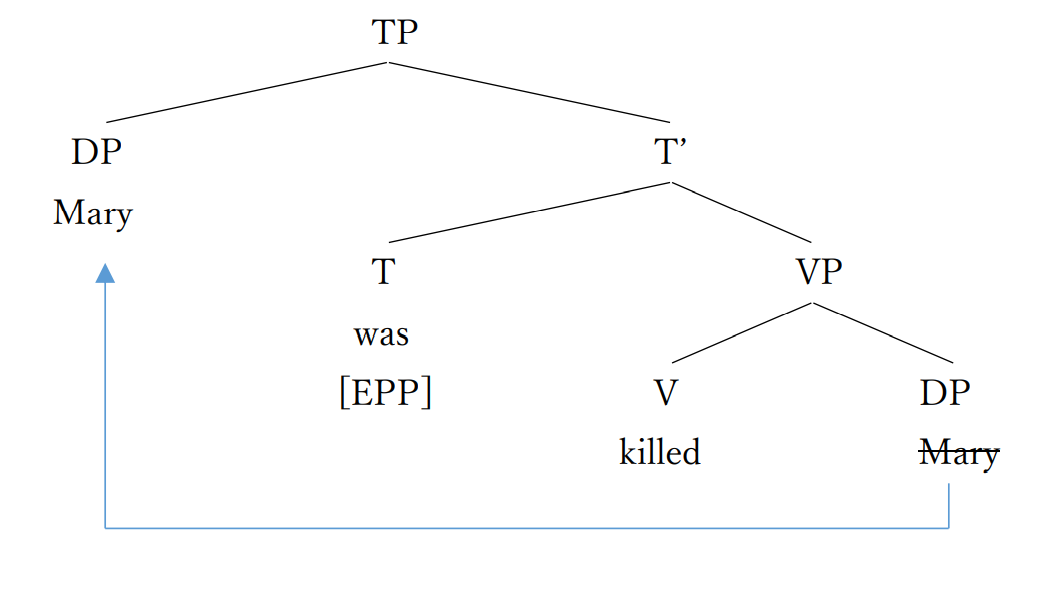

We will see how to make a passive sentence. We make (30) Mary was killed repeated here as (33).

(33) Mary was killed.

First, we merge a V killed and a DP Mary to form the VP killed Mary. The V killed assigns the theta-role of THEME to the c-commanded DP Mary. Then, we merge a T was with this VP killed Mary to form the T-bar was killed Mary. As we have already seen, all Ts in English have EPP features (Radford 2009). A head with the EPP feature must have a specifier. Thus, the EPP feature of the T attracts the DP Mary inside the VP to the specifier of the TP position. Thus, we have got the whole TP Mary was killed Mary. The internal structure of the TP is shown in the tree diagram below. Keep in mind that the DP Mary in the spec-TP has the same theta-role as the DP Mary inside the VP. This means that once the DP Mary receives its theta-role inside the VP, the DP holds this theta-role and moves to the spec-TP position. This follows theta-role criterion Jackendoff proposed.

(34) The internal structure of the TP Mary was killed Mary.

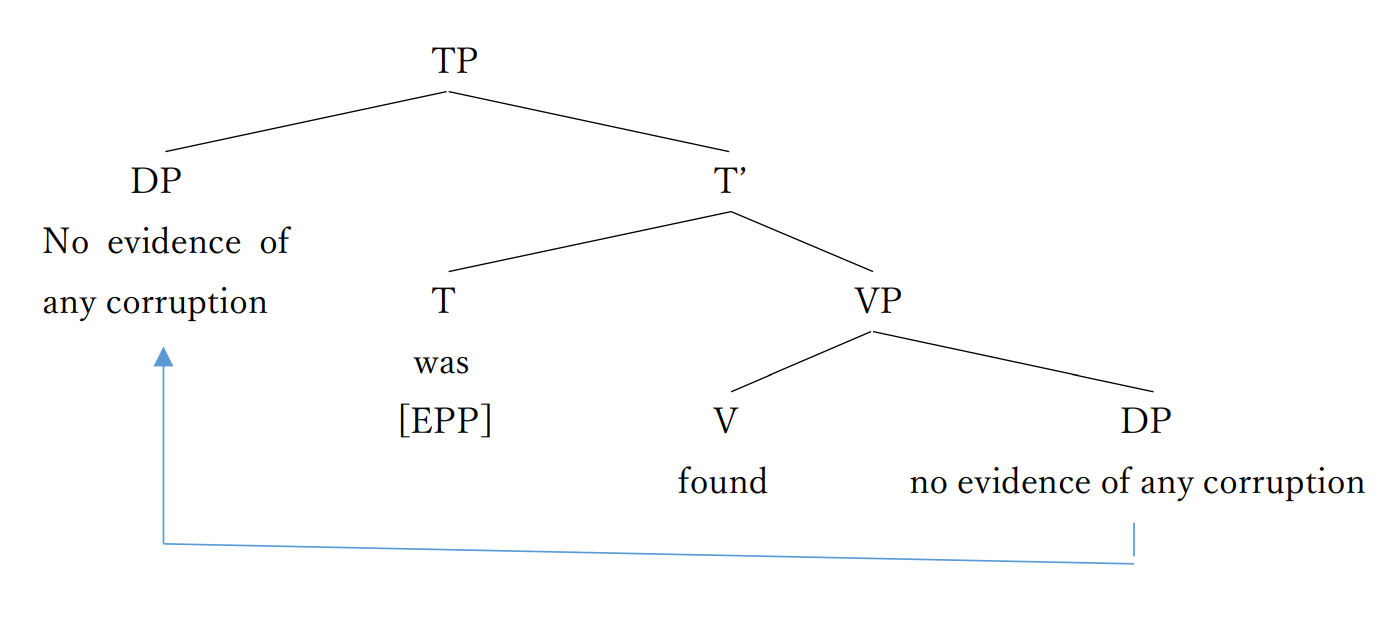

The idea that the DP originally merged as the complement of the V moves to the spec-TP position is supported by the following examples reported by Radford (2009)

(35) No evidence of any corruption was found. (Radford 2009: 256)

(36) There was found no evidence of any corruption. (ibid.)

The meanings of (35) and (36) are virtually the same. We make (35) by the following way. We merge the V found and the DP no evidence of any corruption to form the VP just like the following tree diagram.

(37) The internal structure of (35)

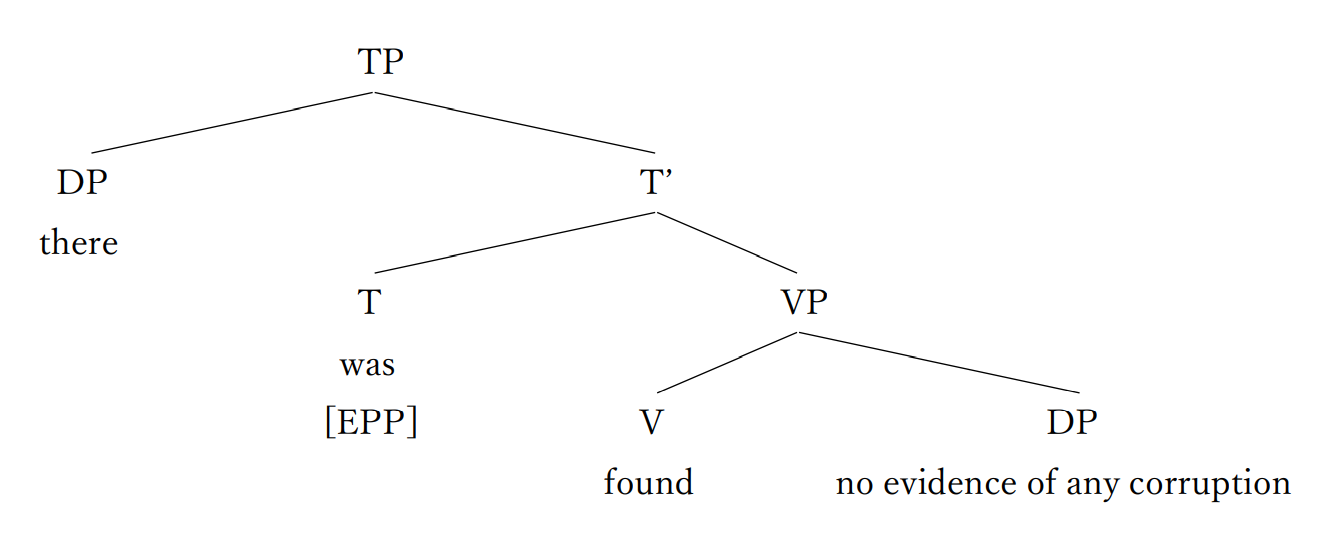

The DP no evidence of any corruption receives its theta-role of THEME from the c-commanding V found. The VP was then merged with the T was to form the T-bar. According to Radford (2009), all Ts in English have EPP features. Thus, the T was must have a specifier. In the cases of (35) and (37), the EPP feature of the T is satisfied by the movement of the DP. However, the requirement of the EPP feature of the T can be satisfied by another way. We merge an expletive there in the specifier of the TP position. In this way, the T has a specifier there. Thus, the EPP feature of the T is satisfied. In this fashion, we get the example (36). The tree diagram in (38) shows the internal structure of (36).

(38) The internal structure of (36).

Chomsky (1995) and Rizzi (2009) claim that movement is a kind of merge. For example, in (37), when we have made the T-bar was found no evidence of any corruption, we take the DP no evidence of any corruption from that T-bar and merge this DP with the T-bar we have already made. Thus, Chomsky (1995) and Rizzi (2009) call movement an internal merge. We take a constituent B from the phrase [A B] we have already built and merge this B with the phrase [A B] to form a larger phrase [B [A B]]. B in the original position is the copy of B. On the other hand, in (38), the expletive there comes from the lexicon (i.e. word stocks) in our brains. The lexicon is outside of the phrase already built (i.e. T-bar). Thus, Chomsky (1995) and Rizzi (2009) call such an operation an external merge. If their claim is correct, we build phrases and sentences only by merger. (Strictly speaking, we also need agreements. However, to simplify things I ignore Agree here.)

References)

Ando, S. (2005) Gendai Eibunnpou Kougi [Lectures on Modern English Grammar]. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Brinton, L. J and Arnovick L. K. (2017) The English Language – A linguistic History. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bybee, J. (2010) Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1955/1975) The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory. New York: Plenum.

Chomsky, N. (1957) Syntactic Structures. Leiden: Mouton & Co.

Chomsky, N. (1980) “On Binding.” Linguistic Inquiry. Vol. 11. No.1. Winter, 1980. pp. 1-46.

Chomsky, N. (1981) Lectures on Government and Binding – The Pisa Lecture. Hague:

Mouton de Gruyter. (origionally published by Foris Publications)

Chomsky, N. (1986) Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995) The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1998) Minimalist Inquiries: The Framework, in Martin, R., Michhaels, D. and Uriagereka, J. (eds.) (2000) Step by Step, Essays on Minimalism in Honor of Howard Lasnik. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2001) “Derivation by Phrase.” In M. Kenstowics, ed., Ken Hale: A life in language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1-52.

Chomsky, N. (2004) “Beyond Explanatory Adaquacy.” In Belleti, A. ed. (2004) Structure and Beyond—The Cartography of Syntactic Structure. Vol.3. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, N. (2005) “Three Factors in Language Design.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 36, Number 1, Winter 2005: 1-22.

Chomsky, N. (2008) “On Phases.” In Freiden, R. Otero, C. P. and Zubizarreta, M. L. eds. (2008) Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory—Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 133-166.

Chomsky, N. (2021) Lecture by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going” Lecture at 161st meeting of Linguistic Society of Japan by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4F9NSVVVuw&t=4738s accessed on 13th May 2022.

Chomsky, N. and Lasnik, H. (1977) “Filters and Control.” Linguistic Inquiry 8: 425-504.

Cinque, G. (2020) The Syntax of Relative clause—A Unified Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donati, C. and Cecchetto, C. (2011) “Relabeling Heads: A Unified Account for Relativization Structures.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 42, Number 4, Fall 2011: 519-560.

Greenberg, G. H. (1963) “Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements”. In Denning, K. and Kemmer, S. (eds.) (1990) Selected Writing of Joseph H. Greenberg. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 40-70.

Inoue, K. (2006) “Case (with Special Reference to Japanese).” in in Everaert, M. and van van Riemsdijk, H.C. (eds.) The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. vol. 1, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 295-373.

Jackendoff, R. (1977) syntax—A Study of Phrase Structure. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Kegl, J., Senghas, A. and Coppola, M. (1999) “Creation through Contact: Sign Language Emergence and Sign Language Change in Nicaragua.” in DeGraff, M. (eds.) (1999) Language Creation and Language Change—Creolization, Diachrony, and Development. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 177-237.

Langacker, R. W. (1991) Foundation of Cognitive Grammar– Descriptive Application. Vol 2 Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Radford, A. (1988) Transformational Grammar – A First course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2004) Minimalist Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2009) Analyzing English Sentences – a Minimalist Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2016) Analyzing English Sentences. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rizzi, L. (2009) “Movements and Concepts of Locality.” in Piattelli-Palmarini, M., Uriagereka, J. and Salaburu, P. (eds.) (2009) Of Minds and Language—A Dialogue with Noam Chomsky in Basque Country. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, I. (2007) Diachronic Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, I. (2021) Diachronic Syntax. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sheehan, M., Biberauer, T., Roberts, I. and Holmberg, A. (2017) The Final-Over-Final Condition—A Syntactic University. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

2件のコメント

コメントは受け付けていません。