Hiroaki Teraoka

July 22th, 2022.

This is a reproduction of the PDF file I published on this blog on 22th July, 2022. The PDF file is difficult to read if you do not download it. Thus, I reproduce the contents of the PDF file here for those who do not want to download the file. I had to change some minor points because underlines and bar notations are unavailable on Word Press.

Sections 1-2 are available from the below link.

3 How did Generative Grammarians Explain Greenberg’s Universals?

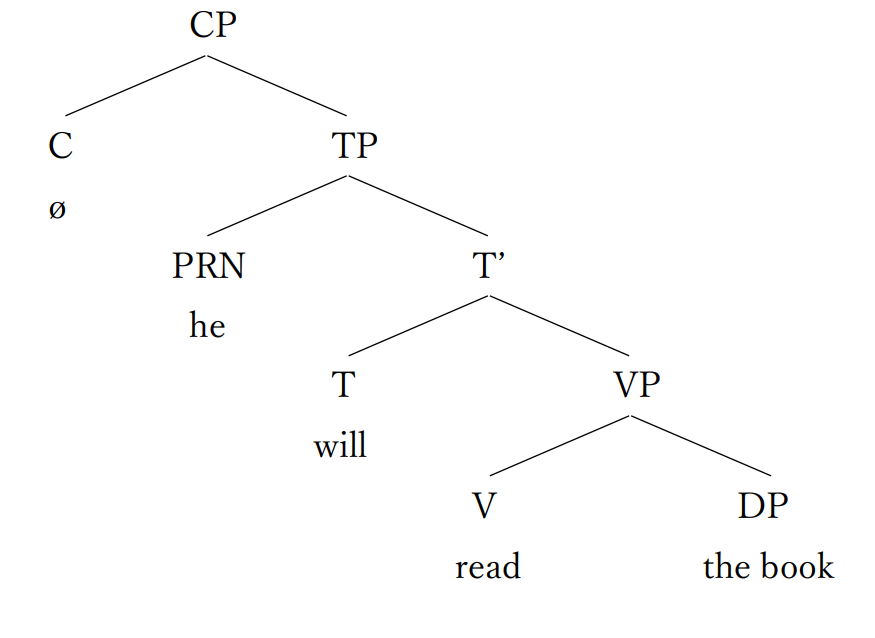

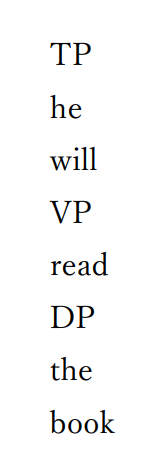

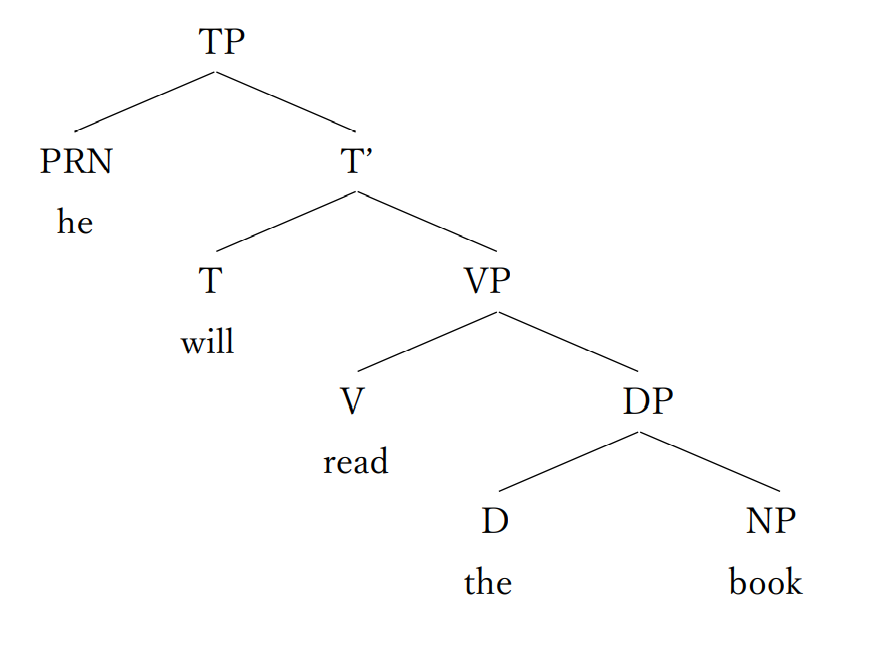

In the preceding section, we saw how generative grammarians analyze sentences. In this section, we see how they have explained some of Greenberg’s universals. One of the most fundamental parameters of human languages is the head-initial parameter (Roberts 2007, 2021). VO type languages has the positive value for this head-initial parameter. In head-first type languages, a head precedes its complement in every phrase. Thus, the head D precedes its complement, NP. The head V precedes its complement, DP. Thus, we have OV word orders in a head-initial type language. The head T precedes its complement, VP. The head C precedes its complement, TP. English has the positive value for the head-first parameter. English sentences have internal structures shown in the following tree diagrams.

(13) (a) He will read the book.

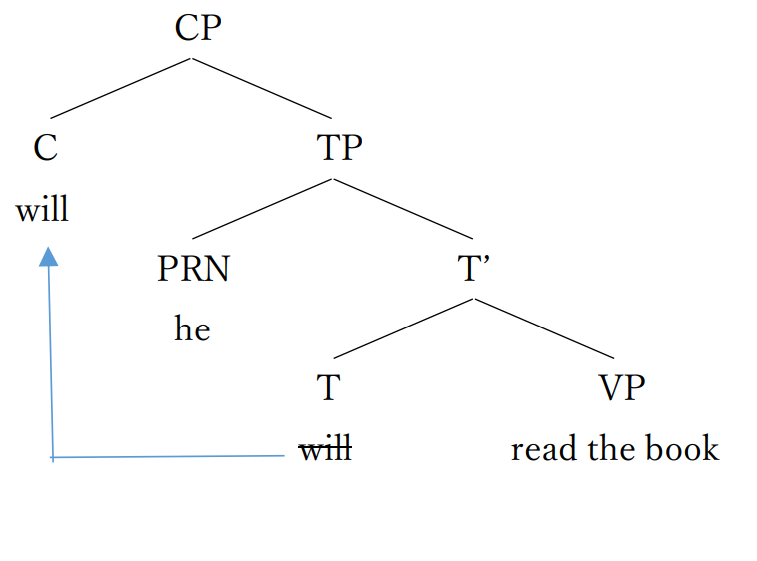

(b) Will he read the book?

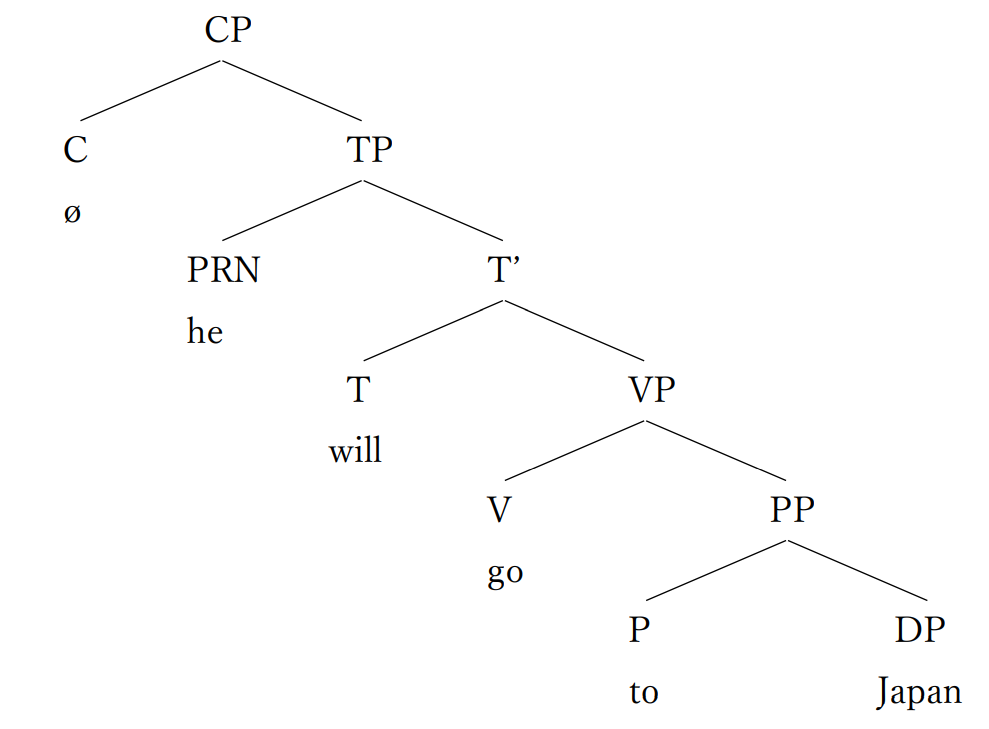

(c) He will go to Japan.

(14) (a) The internal structure of he will read the book (13a)

(b) The internal structure of Will he read the book (=13b)

In the above tree diagram, the constituent in T moves to the head C position. We will see T-to-C movement in section 5

(c) The internal structure of he will go to Japan (=13c)

(PP stands for preposition phrase (PPs). Prepositions are heads of PPs. Prepositions and postpositions belong to adpositions. In a postposition construction, postposition is the head of the postposition phrase. The DP is the complement of the postposition.)

Since English has the positive value for the head-initial parameter, in every phrase (i.e. CP, TP, VP, DP, PP), the head precedes its complement. V precedes its object. A preposition is the grammatical head and the DP governed by the preposition is its complement. A question particle tends to be in the C position. Thus, the question particle tends to be in a clause initial position as Greenberg (1963) observed. Summarizing, we can explain some of Greenberg’s universals by introducing the head-initial parameter.

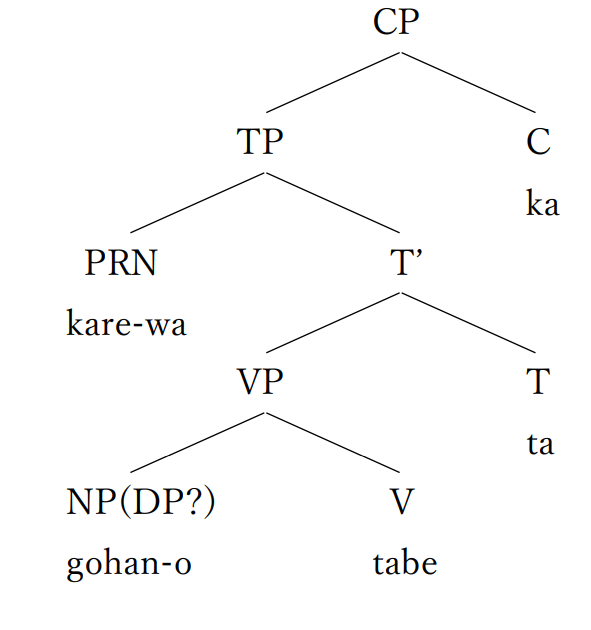

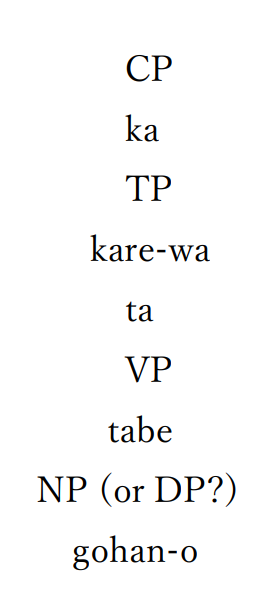

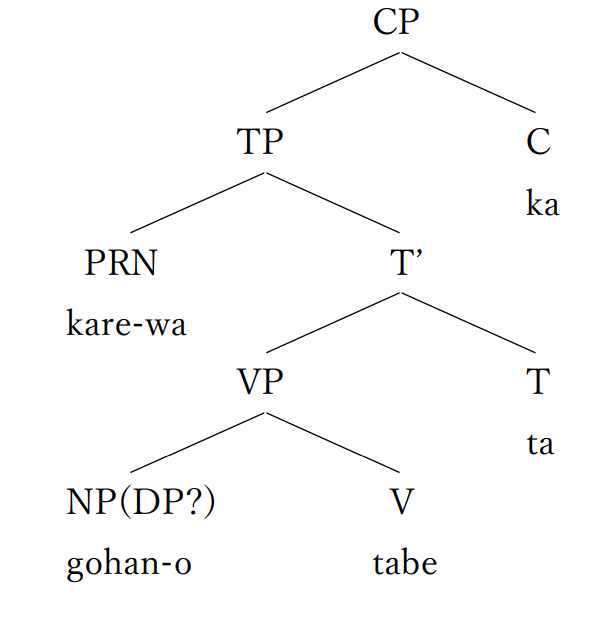

In a language which has the negative value for head-initial parameter, a head follows its complement in every phrase. Japanese is such a language. (In Japanese determiners precedes their complements, NPs.) Japanese has OV word orders and postposition constructions. A postposition is the grammatical head of the postposition phrase. The DP governed by the postposition is the complement. In a postposition phrase, the head follows its complement. The following tree diagram shows the internal structure of a Japanese sentence.

(15) kare-wa gohan-o tabe-ta ka

he-NOM. rice-ACC. eat-PAST. Question

‘did he eat rice?’

(16) The internal structure of (15)

I have no background knowledge about Japanese grammar. I followed Inoue’s (2006) analysis here and placed ta in the head T position. I am not sure where the question particle ka is placed. I put it in the head C position following my intuition. Keep in mind that in a head-final type language, verbs follow objects and Cs follow TPs. Summarizing, the value of the head-initial parameter explains Greenberg’s universal about basic word orders. It is unclear from the above tree diagram (16) whether the specifier of the TP, namely, the pronoun kare-wa, is pronounced before the complement of the V, namely, NP gohan-o, or not. In the following section, I give a purely theoretic answer to this question. However, the following section is difficult. You do not need to worry. You can skip the following section and move on to the section 6.

4. Why do We Need Parameters?

You may wonder why human languages have the head-initial parameter and other parameters. Chomsky (2021) claims that spoken languages need to have word orders because you cannot pronounce two or more words at the same time. Chomsky (1995) and Sheehan, Biberauer, Roberts, and Holmberg, (2017) claim that syntax has only a hierarchic structure shown in (A) and recognizes categories of words but does not have a linear order.

(A)

The hierarchic structure (which has no linear order) is sent to the phonological component (PF). In PF, the hierarchic structure gets the linear order purely for pronunciation reasons I mentioned earlier. The word order of a head and its complement is one of the most fundamental of all word orders (Roberts 2021). Chomsky (1995) also claims that we need to decide on the linear order between a X-bar (an intermediate projection) and its specifier. However, Sheehan, Biberauer, Roberts, and Holmberg (2017) argue that in almost all languages, a specifier precedes the intermediate projection (X-bar). SBRH point out that a subject is associated with the specifier of TP (or VP). Since Greenberg (1963) found out that subjects preceded objects in almost all languages, SBRH concludes that specifiers precede the intermediate projections they merge with. Chomsky (1995) and Sheehan, Biberauer, Roberts, and Holmberg (2017) argue that in the English language, the words sent to the PF are spelled out in the order of specifier-head-complement. When you pronounce the words in (A) in this linear order, you get the below tree diagram (B).

(B)

First, we check the top of the hierarchic structure, namely, the TP. The TP has the specifier, namely, the pronoun he. Following the spell out order in English mentioned earlier, we pronounce the specifier before spelling out the T-bar. Since the value of the head initial parameter is positive in English, we spell out the head of the TP, namely, T will before we pronounce the complement of the T, namely, the VP. The VP is a phrase. Thus, we pronounce the words in the VP following the spell out order mentioned above, namely, the order of specifier-head-complement. The VP has no specifier. Thus, we spell out the head of the VP, namely, V read. After that, we move on to the DP.

Japanese has the opposite value for the head-initial parameter. We will see how we get the word order of (15) from the hierarchic syntax structure in (C).

(C)

Since Japanese has the negative value for the head initial parameter, we spell out a head and its complement in the order of complement-head in the PF. The linear order between a specifier and the intermediate projection (X-bar) is the order in which the specifier precedes the intermediate projection which the specifier merges with. Thus, in Japanese, we spell out words sent to the PF in the linear order of specifier-complement-head. Following this spell out rule, we assign the linear order to the hierarchic syntactic structure in (C). The top of the hierarchic structure is the CP. Since the CP has no specifier, we concentrate on the linear order of the C and its complement. Following the spell out rule I mentioned earlier, we must pronounce the complement of the C before we spell out the C head ka. Since the complement of the C is the TP, we concentrate on the linear order of the words in the TP. Following the spell out order of specifier-complemet-head, we spell out the specifier of the TP, namely, kare-wa, before we pronounce the T-bar. In the T-bar, the complement of the T, namely, the VP, is pronounced before we spell out the head T ta. In the VP, we pronounce the complement of the V, namely the NP, before we spell out the head V tabe. In this fashion, we get the following word order (D, E), which is the same as (15, 16).

(D) kare-wa gohan-o tabe-ta ka (=15)

he-NOM. rice-ACC. eat-PAST. Question

‘did he eat rice?’

(E)

Summarizing, syntax has only a hierarchic structure and recognizes the category each word belongs to but does not have linear word orders. When this hierarchic structure in the syntax is sent to the phonological component (PF), we assign a linear word order to this hierarchical structure following the spell out order. This spell out order follows the values of parameters such as the head-initial parameter. The reason the PF must assign linear order to the words is that in spoken languages, we cannot pronounce two or more words at the same time.

The idea that the syntax has no linear word order but recognizes hierarchic structure and categories of the words is supported by naturally developed sign languages. Idioma de Signos Nicaragüense is one of these naturally developed sign languages. Deaf children in Nicaragua made this new sign language spontaneously (Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola 1999, Roberts 2021). In sign languages, sometimes you can sign two items at the same time. For example, in ISN, what is signed by raised eye braws and backward tilt of your head. You mainly sign with your hands and arms. Thus, two items can appear when what is signed. The signers sometimes sign two items. This fact supports Chomsky’s claim that the syntax has no word order.

In the next section, we look at argument structures and theta-roles.

Sections 5-6 are available from the below link.

References)

Ando, S (2005) Gendai Eibunnpou Kougi [Lectures on Modern English Grammar]. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Brinton, L. J and Arnovick L. K. (2017) The English Language – A linguistic History. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bybee, J. (2010) Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1955/1975) The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory. New York: Plenum.

Chomsky, N. (1957) Syntactic Structures. Leiden: Mouton & Co.

Chomsky, N. (1980) “On Binding.” Linguistic Inquiry. Vol. 11. No.1. Winter, 1980. pp. 1-46.

Chomsky, N. (1981) Lectures on Government and Binding – The Pisa Lecture. Hague:

Mouton de Gruyter. (origionally published by Foris Publications)

Chomsky, N. (1986) Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995) The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1998) Minimalist Inquiries: The Framework, in Martin, R., Michhaels, D. and Uriagereka, J. (eds.) (2000) Step by Step, Essays on Minimalism in Honor of Howard Lasnik. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2001) “Derivation by Phrase.” In M. Kenstowics, ed., Ken Hale: A life in language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1-52.

Chomsky, N. (2004) “Beyond Explanatory Adaquacy.” In Belleti, A. ed. (2004) Structure and Beyond—The Cartography of Syntactic Structure. Vol.3. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, N. (2005) “Three Factors in Language Design.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 36, Number 1, Winter 2005: 1-22.

Chomsky, N. (2008) “On Phases.” In Freiden, R. Otero, C. P. and Zubizarreta, M. L. eds. (2008) Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory—Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 133-166.

Chomsky, N. (2021) Lecture by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going” Lecture at 161st meeting of Linguistic Society of Japan by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4F9NSVVVuw&t=4738s accessed on 13th May 2022.

Chomsky, N. and Lasnik, H. (1977) “Filters and Control.” Linguistic Inquiry 8: 425-504.

Cinque, G. (2020) The Syntax of Relative clause—A Unified Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donati, C. and Cecchetto, C. (2011) “Relabeling Heads: A Unified Account for Relativization Structures.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 42, Number 4, Fall 2011: 519-560.

Greenberg, G. H. (1963) “Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements”. In Denning, K. and Kemmer, S. (eds.) (1990) Selected Writing of Joseph H. Greenberg. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 40-70.

Inoue, K. (2006) “Case (with Special Reference to Japanese).” in in Everaert, M. and van van Riemsdijk, H.C. (eds.) The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. vol. 1, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 295-373.

Jackendoff, R. (1977) syntax—A Study of Phrase Structure. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Kegl, J., Senghas, A. and Coppola, M. (1999) “Creation through Contact: Sign Language Emergence and Sign Language Change in Nicaragua.” in DeGraff, M. (eds.) (1999) Language Creation and Language Change—Creolization, Diachrony, and Development. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 177-237.

Langacker, R. W. (1991) Foundation of Cognitive Grammar– Descriptive Application. Vol 2 Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Radford, A. (1988) Transformational Grammar – A First course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2004) Minimalist Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2009) Analyzing English Sentences – a Minimalist Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2016) Analyzing English Sentences. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rizzi, L. (2009) “Movements and Concepts of Locality.” in Piattelli-Palmarini, M., Uriagereka, J. and Salaburu, P. (eds.) (2009) Of Minds and Language—A Dialogue with Noam Chomsky in Basque Country. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, I. (2007) Diachronic Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, I. (2021) Diachronic Syntax. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sheehan, M., Biberauer, T., Roberts, I. and Holmberg, A. (2017) The Final-Over-Final Condition—A Syntactic University. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

3件のコメント

コメントは受け付けていません。