Hiroaki Teraoka

This work was first presented as the term paper for a sociolinguistic course in June 2022.

Introduction—nature or nurture?

Linguists have long been debating over the mechanism of the first language acquisition. Some linguists claim that children acquire their first languages by imitating their parents’ speech, and others adopt the innate hypothesis. In the innate hypothesis, linguists believe that we have the source of language inside our brains. Noam Chomsky (1995) calls this source of language “universal grammar (UG).” When activated, UG grows into a full language. In this essay, I follow Noam Chomsky and other generative grammarians and argue that the innate hypothesis is valid. In the following section, I introduce a language creation case in Nicaragua as a piece of supporting evidence of the innate hypothesis. If, as some linguists claim, children acquire their first language by imitating languages their parents speak, what happens when they have no language to imitate. This is exactly what happened to the deaf communities in Nicaragua.

a Language Creation Case in Nicaragua

Nicaragua is in Central America. Other countries in Central America are Cuba and Mexico. A dictatorship government governed Nicaragua until 1979. The dictatorship government did not provide any care for deaf people. According to Roberts (2021) and Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola (1999), deaf community in Nicaragua did not have any common sign languages. Deaf children in Nicaragua could not read lips. They used very simple phrase level expressions called ‘homesigns.’ ‘Homesigns’ were able to be understood only in their homes. Thus, the homesign of one deaf household was different from that of another.

The dictatorship government in Nicaragua collapsed in 1979. A new government provided care for deaf children in Nicaragua. The new government built a school for deaf children. About 500 deaf children with different homesigns came to the school. The teachers of the school tried to teach the deaf children Spanish, which was an official language in Nicaragua. However, the teachers’ efforts ended in failure mainly because the deaf children could not read lips (Roberts 2021).

According to Roberts (2021), soon after the deaf children came to the school, they tried to communicate with each other and they invented a kind of pidgin language. A pidgin is an artificial language made by speakers of different languages in contact situations to communicate with each other (Romaine 1988). Typically, a pidgin has a simplified grammar and its vocabulary is made from words of the original languages. Two to three years later, the deaf children in Nicaragua made a new common sign language from this simple pidgin. The new language had a very complicated grammar. This new language had tenses, aspects, wh-question sentences, yes-no question sentences, relative clauses, topicalizations and even case markings for nominative, accusative and locative cases (Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola 1999). Spanish does not distinguish any cases for nouns. Thus, this new sign language was completely different from Spanish, which was a language of the deaf children’s parents.

The name of this new language is Idioma de Signos Nicaragüense (ISN). In this section, I introduce some examples of the new sign language in Nicaragua. The new language uses serial verb constructions when a sentence has two arguments. According to Radford (2009), each sentence has a predicate which depicts an action or an event. Arguments are participants of the events or actions described by the predicate.

(1) He runs.

(2) He ate the cake.

In (1), he is the argument. According to Radford (2009), each argument has only one theta-role (semantic role). He in (1) can intentionally start and stop the action described by the verb run. Thus, he in (1) has the theta-role of AGENT. On the other hand, the example in (2) has two arguments, namely, the person who ate and the thing which was eaten. He in (2) also has the theta-role of AGENT. The cake has the theta-role of THEME.

In the following examples of ISN in (3), each sentence has the meaning of ‘the woman pushed the man’ (Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola 1999)

(3) (a). WOMAN PUSHE MAN GET-PUSHED

‘The woman pushed the man’

[lit. ‘The woman pushed the man (man) got pushed’] (Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola 1999 : 217)

(b). WOMAN PUSH MAN REACT

[lit. ‘The woman pushed the man (man) reacted’] (ibid.)

(c). WOMAN PUSH MAN FALL

[lit. ‘The woman pushed the man (man) fell’] (ibid.)

Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola (1999) claims that the signers used the second verbs to indicate that the second noun (i.e. MAN) is the second argument.

Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola (1999) also observed that the new sign language is developing the true transitive verb constructions. Santos was brought up by his uncle and aunt, both of whom use this new sign language (Idioma de Signos Nicaragüense). Santos (who was 7 when researched) signed the following example.

(4) WOMAN PUSH MAN (NP V NP)

‘The woman pushed the man.’ (Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola 1999: 219)

The sentence in (4) lacks the second verb. Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola (1999) interpret this data as the fact transitive verb is stabilizing in ISN.

As I mentioned earlier, the new sign language (ISN) has topicalization constructions. In topicalization, you move a noun phrase to the front of the sentence to emphasize it.

(5) (a) I failed the exam.

(b) The exam, I failed.

In (5b), the exam is moved to the sentence initial position to be topicalized. Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola (1999) observed similar phenomena in the new sign language in Nicaragua.

(6) MAN,, WOMANPUSH (MAN) GET-PUSHED

‘The woman pushed the man.’ (Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola 1999 : 218)

(7) MAN GET PUSHED, WOMAN PUSH ((MAN) GET-PUSHED)

‘The woman pushed the man.’ (ibid.) Both (6) and (7) shows that the new language has topicalizations.

Language Acquisition from Generative Perspective—Parameter Setting

The language creation case in Nicaragua clearly shows that “the source of language is within us” (Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola 1999, 223). We already know that generative grammarians call this source of language universal grammar. The reasonable question is how we make a full language out of this universal grammar.

We suppose that UG has parameters and children set the values of the parameters of UG. No linguist knows the exact number of parameters a human language has. Roberts (2007) claims that human language has about 30-100 parameters. However, recent study shows human languages have a larger number of parameters (Roberts 2021). As an example of a parameter, I introduce the head-initial parameter.

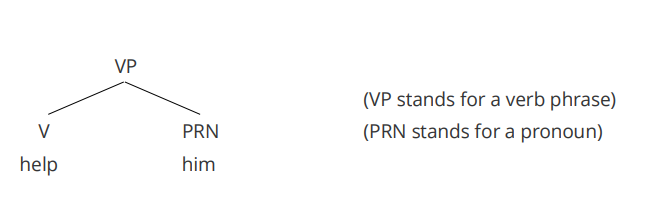

The head-initial parameter shows the position of a head inside a phrase. We can decompose any phrase and sentence of human language into smaller constituents (i.e. parts). For example, we can decompose a verb phrase into two constituents, namely, a verb help and a pronoun him. A phrase has a head which determines the grammatical feature of the overall phrase. In the case of the verb phrase help him, the verb help determines the grammatical feature of the overall phrase and this is the head of the verb phrase. On the other hand, the pronoun him does not determine the grammatical feature of the overall phrase. Linguists call such a constituent a complement. Thus, in the case of the verb phrase help him, the pronoun him is the complement.

(8) The internal structure of the verb phrase help him.

Notice that only two ways of word orders are possible for a head and its complement. One way is that you place the head and its complement so that the head precedes its complement. The other way is that you arrange them so that the head follows the its complement. The value of the head-initial parameter govern the order of the head and its complement. A parameter has only positive or negative values. Thus, a parameter has no intermediate value. Once a child set the value of the head-initial parameter as positive, all the phrases he produces have the head-first word orders. Thus, in every phrase he utters, a head precedes its complement. In a verb phrase, the verb always precedes its object.

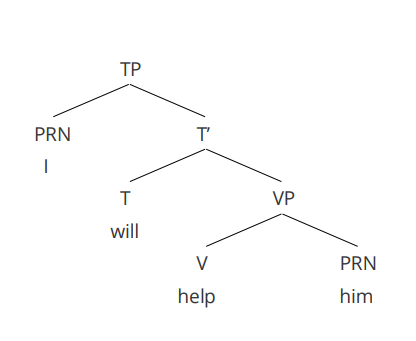

As the next step we merge this VP with a tense constituent (T). Noam Chomsky (1995) put forward the concept of merger. Merge combines two constituents (i.e. a word or a phrase) to form a larger phrase. In fact, we have already merged the V help with the pronoun him to form the VP help him. Now, we merge this VP with the T (tense) will to form a T-bar will help him.

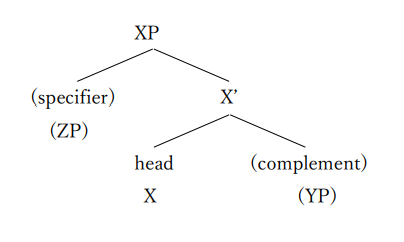

The reason the attained phrase will help him is not a full TP (tense phrase) is as follows. As Jackendoff (1977) claims, the internal structure of a phrase can be diagramed as the following tree diagram shows.

(9) The internal structure of a phrase.

I adopt and modify Jackendoff’s (1977) claim. The head X and its complement YP merges to form the X-bar. This X-bar merges with the specifier (YP) to form a full phrase XP. The X-bar is larger that the head X but smaller than the full phrase XP. Thus, the X-bar is called an intermediate projection. Linguists call the XP a maximal projection. Jackendff (1977) thought that the grammatical feature of the head X is projected upward through the intermediate projection (X-bar) to the maximal projection (XP). Hence he named X-bar and XP projections of the head X. Keep in mind that the specifier and complement are optional. When the phrase lacks the specifier but complete, the phrase is already the maximal projection. When the phrase lacks both the specifier and the complement, the head is the maximal projection.

In the case of the T-bar will help him, this phrase is somehow incomplete. Thus, as Radford (2009) claims, Ts in English need specifiers. Thus, we need to merge a pronoun such as I with this T-bar to form a full TP I will help him.

(10) The internal structure of the TP I will help him.

Thus far, all the head (I.e. the T will and the V help) precede their complements (i.e. the VP help him and the pronoun him). This in not by chance. English is a head-first type language. The value of the head-first parameter governs the word orders of a head and its complement in English. Small children acquiring English realize that English is a head-first type language and he sets the positive value for the head-first parameter in his brain.

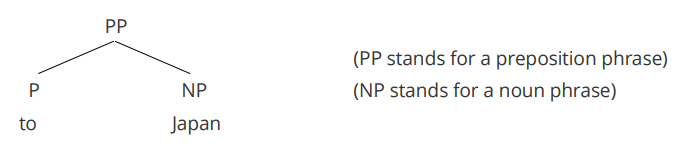

A language tends to show consistent word orders for the value of a parameter. For example, as we have seen above, English has the positive value for the head-initial parameter. This means that not only Ts and Vs, but also prepositions show head-initial word order. Prepositions determine the grammatical features of preposition phrases (PPs). Thus, prepositions are the heads of the preposition phrases. Nouns governed by the prepositions are complements of the prepositions. Prepositions and postpositions belong to adpositions. In a head-last language such as Japanese, adpositions appear as postpositions.

(11) The internal structure of a preposition phrase (PP).

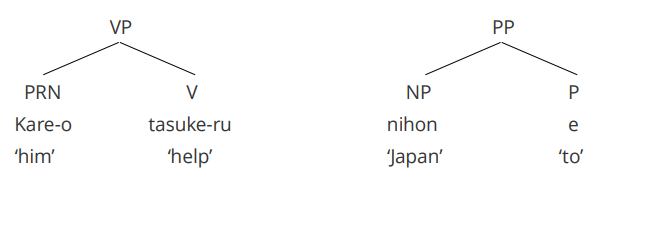

On the other hand, when a child set the value of the head-initial parameter as negative, in every phrase he produces, the head follows its complement. In the case of a verb phrase, the verb always follows its object. Such a language has postposition constructions. Japanese belongs to head-final type languages. For example, the following Japanese phrases have head-final word orders. Both heads tasuke-ru ‘help’ and e ‘to’ follow their complements.

(12) Japanese

(a) Kare-o tasuke-ru

him help

‘help him’

(b) nihon-e

Japan to

‘to Japan’

(13) The internal structures of a verb phrase and a postposition construction in Japanese, which is a head-final language.

Word orders are so simple that generative grammarians such as Chomsky (1995) and Roberts (2021) claim that the task of acquiring the grammar of your first language is just setting the values of the parameters of Universal Grammar. Biologically, we all have UG. If we suppose that children are just setting parameters of Universal Gramma, they do not need vast amounts of memory loads. A child realizes which type of language his target language belongs to and sets the values of his parameters of Universal Grammar. This model of the first language acquisition explains why children master their first languages in such a short time despite the fact that adults cannot acquire foreign languages at native levels. The parameter setting abilities fade as you mature.

Things we learn from the language creation case in Nicaragua is that children set the values of their parameters even when they cannot access a full language. The deaf children in Nicaragua only had different ‘homesigns’ and a pidgin language made from the homesigns. These homesigns and a pidgin made from the homesigns might have had inconsistent parameter settings. For example, homesign A had a head initial word orders but homesign B had head last word orders. The pidgin made from these homesigns might have had object-verb word orders for some verbs but verb-object word orders for other verbs. The pidgin might have lacked several functional categories such as tenses and aspects. The deaf children made a full sign language out of this ‘incomplete’ language. This shows that the children had universal grammar and they set parameters of UG on their own. A reasonable question here is what is crucial for setting parameters. Roberts (2021) interprets this language creation case as a creolization. When small children acquire a pidgin as their native language, the pidgin grows into a creole. A creole is a full-fledged language which has grammatical categories other naturally developed languages have (Roberts 2021). By naturally developed languages, I mean languages which have native speakers. Computer programming languages and Esperanto are not naturally developed languages, but artificial languages. Linguists know that almost all naturally developed languages have tenses, aspects, yes-no questions, wh-questions, relative clauses, and causative constructions. Almost all creoles have these grammatical categories. Following Roberts (2021), I claim that the new sign language in Nicaragua (ISN) is also a creole. ISN and other creoles show that we do not need a language to make a language. We possess Universal Grammar biologically and set parameters of UG even when we do not have access to any full-fledged language to imitate. However, Roberts (2021) and Kegl, Senghas, and Coppola (1999) claim that we need communities. Small children set parameters when they try to communicate with each other. Exactly same situation is observed in Nicaragua’s deaf community. When they came to the school, they tried to communicate with each other even though they had different homesigns. This enabled them to set parameters in their brains. As I mentioned earlier, these parameter setting abilities fade as you mature. In the following section, I discuss what happened to the deaf students who entered the school after they had already lost their abilities to set parameters.

Critical Period for First Language Acquisition

Kegl, Senghas and Coppola (1999) shows that the age of entry to the school was crucial. Their research shows that most students who entered the school under 7 attained the native level proficiencies for the new sign language. On the other hand, students who entered the school between 7-14 years old did not attain the native level proficiencies. Kegl, Senghas and Coppola (1999) compared the number of signs each student made per minute. The students who joined the deaf community before they reached 7 usually made more than 40 signs per minute. On the other hand, students who joined after they reached 7 usually made only about 20 signs per minute. This data made Kegl, Senghas and Coppola (1999) conclude that the age of 7 is the critical period for first language acquisition. The student who entered the school between 7 to 14 years old acquired the new language well but they never reached native levels. The most crucial cases are students who joined the deaf community after they reached 15. Roberts (2021) claims that they never acquired the new sign language. They continued to use homesigns.

Kegl, Senghas and Coppola (1999) also compared the sentence structures of the sign language made by students who entered the school at different ages. Kegl, Senghas and Coppola (1999) show that a student who entered the school in very early age (4 years old) produced topic-NP V constructions in 13 percent of her entire speech (Kegl, Senghas and Coppola 1999: 220). A student who entered the school at 7 also produced topic-NP V constructions in 17 percent of his entire speech (ibid.). On the other hand, a student who entered the school at 9 produced none of topic-NP V constructions (ibid.). This data shows that the age of 7 is the critical period for first language acquisition. The difference between the two students who entered the school under 7 is minimal. However, the difference between 7 and 9 is crucial.

Conclusion

The language creation case in Nicaragua supports the innate hypothesis. Children acquire their first languages not by imitation but by setting parameters of UG. Children set parameter by trying to communicate with each other. Thus, they do not necessarily need a full-fledged language but need communities to acquire their first languages.

References)

Ando, S (2005) Gendai Eibunnpou Kougi [Lectures on Modern English Grammar]. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Chomsky, N. (1995) The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2005) “Three Factors in Language Design.” Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 36, Number 1, Winter 2005: 1-22.

Chomsky, N. (2021) Lecture by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going” Lecture at 161st meeting of Linguistic Society of Japan by Noam Chomsky “Minimalism: where we are now, and where we are going.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4F9NSVVVuw&t=4738s last accessed on 13th July 2022.

Jackendoff, R. (1977) syntax—A Study of Phrase Structure. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Kegl, J., Senghas, A. and Coppola, M. (1999) “Creation through Contact: Sign Language Emergence and Sign Language Change in Nicaragua.” in DeGraff, M. (eds.) (1999) Language Creation and Language Change—Creolization, Diachrony, and Development. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 177-237.

Radford, A. (1981) Transformational Syntax—A Student’s Guide to Chomsky’s Extended Standard Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2009) Analyzing English Sentences – a Minimalist Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, A. (2009) Analyzing English Sentences – a Minimalist Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, I, (2007) Diachronic Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, I. (2021) Diachronic Syntax. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Romaine, S. (1988) Pidgin & Creole Languages, London: Longman.

Further Reading)

Roberts (2021) is an introductory textbook which deals with the language creation case in Nicaragua. Roberts consider ISN as a creole.

Kegl, Senghas and Coppola (1999) is the first literature on ISN. Those who are interested in this topic must read this article.

1件のコメント

コメントは受け付けていません。